British T-class submarine

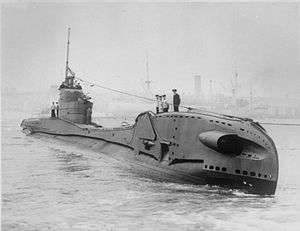

HMS Thorn | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | T class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Grampus class |

| Succeeded by: | U class |

| Completed: | 53 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 276 ft 6 in (84.28 m) |

| Beam: | 25 ft 6 in (7.77 m) |

| Draught: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Range: | 8,000 nmi (9,200 mi; 15,000 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) surfaced with 131 tons of fuel[1] |

| Complement: | 48 |

| Armament: |

|

The Royal Navy's T class (or Triton class) of diesel-electric submarines was designed in the 1930s to replace the O, P, and R classes. Fifty-three members of the class were built just before and during the Second World War, where they played a major role in the Royal Navy's submarine operations. Four boats in service with the Royal Netherlands Navy were known as the Zwaardvisch class.

In the decade following the war, the oldest surviving boats were scrapped and the remainder converted to anti-submarine vessels to counter the growing Soviet submarine threat. The Royal Navy disposed of its last operational boat in 1969, although it retained one permanently moored as a static training submarine until 1974. The last surviving boat, serving in the Israel Sea Corps, was scrapped in 1977.

Design and development

Design began in 1934 but was constrained by the 1930 London Naval Treaty restricting the total British submarine fleet to 52,700 tons, a maximum of 2,000 tons for any boat, and maximum armament of one 5.1 in (130 mm) gun. The "Repeat P"s, as the design was originally called, were intended to be large and powerful enough to operate against Japan in the absence of other British naval units. Britain was in a financial crisis and would have difficulty affording enough boats to meet their allowance.

It was expected from British work on ASDIC that other nations would develop something similar. To that end a smaller vessel around 1,100 tons would avoid detection. In the face of expected enemy anti-submarine measures any attack would probably have to be made at long range without the aid of the periscope but on ASDIC. To counter the resultant inaccuracy a large salvo of at least eight torpedoes would be needed.[2]

The eventual design had 8 bow torpedo tubes (two external), two external tubes amidships angled to fire forward, and a single 4-inch (100 mm)/50 caliber deck gun. Maximum operational diving depth was 300 ft (91 m) with an estimated crush depth of 626 ft (191 m).[3] The design was finalised in 1935 and on June 24 the decision was made to drop the "Repeat P" designation and give all boats names starting with "T".

The ten-torpedo salvo was the largest ever fitted to an operational submarine.[4] British operational planning at the time assumed international treaties would prevent unrestricted submarine warfare, and the main purpose of the submarine would be to attack enemy warships. In such a situation, a commander may have only one chance to attack, so a large salvo was essential. T-class boats built later in the war changed the two amidships tubes to fire astern.

The lead boat, Triton, was ordered on 5 March 1936 and ran her first-of-class trials in December 1938. Fifty-three T-class submarines were built before and during the war in three distinct groups, although there were minor differences between boats within the same group. The second and third groups had the fuel capacity increased on many boats to 230 tons, giving a range of 11,000 nmi (20,000 km; 13,000 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1][5]

Service history

T-class submarines fought in all theatres in the Second World War and suffered around 25 percent losses. They were particularly vulnerable in the Mediterranean, where their large size made them easily visible from the air in the clear waters, but they had much more success elsewhere.

After the war, all surviving Group One and Two boats were scrapped and the remainder fitted with snorts.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, most were streamlined for quiet and higher-speed underwater operation against Soviet submarines, in place of the anti-surface-ship role that they had been designed for. In January 1948, it was formally acknowledged that the main operational function of the British submarine fleet would now be to intercept Soviet submarines slipping out of their bases in Northern Russia to attack British and Allied merchant vessels. The following April, the Assistant Chief of Naval Staff, Rear-Admiral Geoffrey Oliver, circulated a paper in which he proposed that British submarines take a more offensive role by attacking Soviet submarines off the Northern Russian coast and mining the waters in the area. With the dramatically reduced surface fleet following the end of the Second World War, he commented that this was one of the few methods the Royal Navy had for "getting to the enemy on his home ground."[6]

Much of the work carried out on the submarines was underpinned by results of measurements made using Tradewind, which had been modified in July 1945 – September 1946 to become an acoustic trials submarine, with external tubes and guns removed, the bridge faired, the hull streamlined and some internal torpedo tubes blanked over.

Starting in 1948, eight newer all-welded boats underwent extensive "Super-T" conversion at Chatham Dockyard. The modifications included the removal of deck guns and the replacement of the conning tower with a "sail", a smooth-surfaced and far more symmetrical and streamlined tower. An extra battery was installed, and a new section of hull inserted to accommodate an extra pair of motors and switchgear. This varied between 14 ft (4.3 m) in the earlier conversions and 17 ft 6 in (5.33 m) in the later ones. These changes allowed an underwater speed of 15 knots (28 km/h) or more and increased the endurance to around 32 hours at 3 knots (6 km/h). The first boats to undergo this modification were Taciturn in November 1948 – March 1951, followed by Turpin in June 1949 – September 1951. The programme was completed with the conversion of Trump in February 1954 – June 1956.

The conversion was not entirely successful since the metacentric height was reduced, making the boats roll heavily on the surface in rough weather. This was alleviated in 1953 in those conversions which had been completed by increasing the buoyancy by raising the capacity of a main ballast tank by 50 tons. This was done by merging it with an existing emergency oil fuel tank. For the four boats remaining to be converted, increase in buoyancy was achieved by lengthening the extra hull section to be inserted from 14 ft (4.3 m) to 17 ft 6 in (5.33 m). The effect was to lengthen the control room and strict instructions were issued that this space was not to be used for extra equipment otherwise the improved buoyancy would be affected.

In the meantime, in December 1950, approval was given for the streamlining of five riveted boats. This was a much less extensive process, with the removal of deck guns and external torpedo tubes, the replacement of the conning tower by a "sail" and replacement of the batteries by more modern versions providing a 23 percent increase in power. The work was much more straightforward than the conversion of the welded boats and was undertaken during normal refit. The first riveted boat to undergo this modification was Tireless in 1951.

The last operational Royal Navy boat of the class was Tiptoe, which was decommissioned on 29 August 1969. The last T class boat in service with Royal Navy, albeit non-operationally, was Tabard, which was permanently moored as a static training submarine at the HMS Dolphin shore-establishment from 1969 until 1974, when she was replaced by HMS Alliance.

The last operational boat anywhere was the INS Dolphin, formerly HMS Truncheon, one of three T-class boats (and two S-class ones) sold to the Israeli Navy;[7] it was decommissioned in 1977.

Another submarine sold to Israel, Totem renamed INS Dakar, was lost in the Mediterranean in 1969 while on passage from Scotland to Haifa. Although the wreck was discovered in 1999, the cause of the accident remains uncertain.

Group One boats

These fifteen pre-war submarines were ordered under the Programmes of 1935 (Triton), 1936 (next four), 1937 (next seven) and 1938 (last three). The boats originally had a bulbous bow covering the two forward external torpedo tubes, which quickly produced complaints that they reduced surface speed in rough weather. These external tubes were therefore removed from Triumph during repairs after she was damaged by a mine and Thetis during the extensive repairs following her sinking and subsequent salvage. Only six survived the war, less than half.

- Triton (sunk in the Adriatic on 18 December 1940)

- Thetis (sank during trials, was salvaged and recommissioned as Thunderbolt; sunk by the Italian corvette Cicogna off Messina Strait on 14 March 1942)

- Tribune

- Trident

- Triumph (lost, probably to Italian mines, on 14 January 1942)

- Taku

- Tarpon (probably sunk by German minesweeper M-6 on 14 April 1940)

- Thistle (torpedoed by U-4 on 10 April 1940)

- Tigris (probably sunk by German ship UJ-2210 on 27 February 1943)

- Triad (sunk by gunfire from the Italian submarine Enrico Toti in the Gulf of Taranto on 15 October 1940)

- Truant

- Tuna

- Talisman (lost, probably to Italian mines, on 17 September 1942)

- Tetrarch, the only boat completed with mine laying equipment (lost, probably to Italian mines, on 2 November 1941)

- Torbay

Group Two boats

These seven vessels were all ordered under the 1939 War Emergency Programme. The first, Thrasher, was launched on 5 November 1940. The external bow torpedo tubes were moved seven feet aft to help with sea keeping. The two external forward-angled tubes just forward of conning tower were repositioned aft of it and angled backwards to fire astern, and a stern external torpedo tube was also fitted. This gave a total of eight forward-facing tubes and three rear-facing ones. All Group Two boats were sent to the Mediterranean, only Thrasher and Trusty returned.

- Tempest (sunk by the Italian Spica class torpedo boat Circe on 13 February 1942)

- Thorn (sunk by the Italian Orsa class torpedo boat Pegaso on 6 August 1942)

- Thrasher

- Traveller (lost, probably to Italian mines, on 12 December 1942)

- Trooper (lost, probably to German mines, on 14 October 1943)

- Trusty

- Turbulent (possibly sunk by an Italian torpedo boat, or a mine in March 1943[8]) During her career, she sank over 90,000 tons of enemy shipping.[9]

Group Three boats

Wartime austerity meant that they lacked many refinements such as jackstaffs and guardrails, and had only one anchor. Much of the internal pipework was steel rather than copper. The first Group Three boat was P311, launched on 10 June 1942. Welding gradually replaced riveting and some boats were completely welded, which gave them an improved rated maximum diving depth of 350 ft (107 m).[10]

- Nine submarines were ordered under the 1940 Programme.

- P311 (lost, probably to Italian mines, before her name Tutankhamen was formally assigned)

- Trespasser

- Taurus (to the Royal Netherlands Navy as Dolfijn)

- Tactician

- Truculent (sunk in collision on 12 January 1950)

- Templar

- Tally-Ho

- Tantalus

- Tantivy

- Seventeen submarines were ordered under the 1941 Programme.

- Telemachus

- Talent (P322) (to the Royal Netherlands Navy as Zwaardvisch)

- Terrapin

- Thorough

- Thule

- Tudor

- Tireless

- Token

- Tradewind

- Trenchant

- Tiptoe

- Trump

- Taciturn

- Tapir (to the Royal Netherlands Navy as Zeehond (2))

- Tarn (to the Royal Netherlands Navy as Tijgerhaai)

- Talent (P337)

- Teredo

- Fourteen submarines were ordered under the 1942 Programme, but only five were completed.

- Tabard

- Totem (lost in accident on passage to Israel as INS Dakar)

- Truncheon (later the Israeli INS Dolphin)

- Turpin (later the Israeli INS Leviathan)

- Thermopylae

The other nine were ordered but cancelled on October 29, 1945 following the end of hostilities:

- Thor (P349) (laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard on 5 April 1943 and launched on 18 April 1944. However, the war ended before she was completed and she was sold for scrapping to Rees Shipbreaking Co Ltd of Llanelli, Wales in July 1946. She would have been the only ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name Thor, after the mythological Norse god of thunder.[11])

- Tiara (also launched on 18 April 1944 at Portsmouth but not completed)

- Theban (P341)

- Talent (P343)

- Threat (P344)

- also four unnamed submarines (P345, P346, P347 and P348).

Transfers to Royal Netherlands Navy

- Tijgerhaai (ex-Tarn)

- Zwaardvisch (ex-Talent)

- Zeehond (2) (ex-Tapir)

- Dolfijn (ex-Taurus)

Notes

- 1 2 Warship III, T Class Submarines, Lambert, p125

- ↑ Brown, D.K. Nelson to Vanguard, p.112.

- ↑ Nelson to Vanguard, D. K. Brown, Chatham Publishing, 2000, ISBN 1-86176-136-8, P.119

- ↑ McCartney, I., British Submarines 1939–1945 (2006) Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84603-007-9, p8

- ↑ Bishop, in The Complete Encyclopedia of Weapons of WW2, p.450, gives 12665nm at 10 knots.

- ↑ Paul Kemp (1990). The T-Class submarine – The Classic British Design. Arms and Armour. p. 127. ISBN 0-85368-958-X.

- ↑ "Israeli T-class submarines". Israeli Submarines. Retrieved 2006-10-29.

- ↑ "HMS Turbulent (N 98)"

- ↑ Submarine History : Submarine Service : Operations and Support : Royal Navy Archived February 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Barrow-in-Furness Branch of the Submariners Association. HMS Tabard.

- ↑ HMS Thor, Uboot.net

References

- Akermann, Paul (2002). Encyclopaedia of British Submarines 1901–1955 (reprint of the 1989 ed.). Penzance, Cornwall: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 1-904381-05-7.

- Bagnasco, Erminio (1977). Submarines of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-962-6.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Kemp, Paul J. (1990). The T-class Submarine: The Classic British Design. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-826-7.

- McCartney, Innes (2006). British Submarines 1939–1945. New Vanguard. 129. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-007-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British T class submarine. |