Barney Oldfield

| Berna Eli Oldfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

January 29, 1878 near Wauseon, Ohio |

| Died |

October 4, 1946 (aged 68) Beverly Hills, California |

| Resting place | Holy Cross Cemetery |

| Other names | Barney Oldfield |

Berna Eli "Barney" Oldfield (January 29, 1878 – October 4, 1946) was an American pioneer automobile racer "whose name was synonymous with speed in the first two decades of the 20th century".[1] He began racing in 1902 and continued until his retirement in 1918. He was the first man to drive a car at 60 miles per hour (96 km/h).[2][3]

Biography

Early life

Berna Eli Oldfield was born in York Township, Fulton County, Ohio, near Wauseon, on January 29, 1878, to Henry Clay, a laborer, and Sarah Oldfield. He was named after his father's bunkmate in the 68th Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War.

As of the 1880 United States Census, the Oldfields (he had a sister, Bertha) lived in Wauseon. In 1889 they moved to Toledo, where Henry got a job at a mental asylum. In the summer of 1891, Berna worked as a waterboy in order to purchase his first bicycle. According to legend, he spent most of his Sunday afternoons at the local Toledo fire station, hoping for the next call. As its “mascot”, he was allowed to ride the big red hose wagon, while a pair of horses raced through the streets. Berna worked the following school year selling the Toledo Blade and Toledo Bee newspapers.

He dropped out of school after the eighth grade in 1892 and started working with his father as a kitchen helper at the mental asylum during the day and a bellhop at the downtown hotel at night. He eventually worked at the hotel full-time as he felt uneasy around mental patients. The bell captain apparently told him that “Berna” was a sissy name, so “Barney” became his official name. Barney, who had a "magnetic personality", received many tips and bought his first bike, an "Advance Traveller" with pneumatic tires.

Bicycle racer

Clarence Brigham, who sold the “Cleveland” brand bike, and Edward G. Eager (of Eager & Green Mercantile) who sold the “Columbia” models in his store, organized the Wauseon Cycle Club to increase sales and draw more people to town on the Michigan Lake Shore Railroad. Other cycling groups in Swanton, Clyde, Monroe, Adrian, Blissfield and Toledo were part of the same cycle racing circuit. Half-mile and mile classes were raced on public tracks usually reserved for horses. Other members included Fred Ballmeyer, Ora Brailey, Curt and Buff Harrison, Doc Myers, Emil Winzeler, Doc Miley, Frank Harper, Dan Raymond (who fixed everyone’s bikes), Sid Black (a trick cyclist from Cleveland who later became president of the Packard Motor Company) and Barney Oldfield. In October 1892, the second “Silver Tournament” was held in Wauseon. In 1893, he began working as an elevator operator at a different hotel. Every night he stored one hotel tenant’s lightweight "Cleveland" cycle in the basement; he sometimes "borrowed it", riding it at night.

Oldfield began bicycle racing in 1894.[4] At age 16, in 1894, he entered his first race and officials from Dauntless bicycle factory asked him to ride for the Ohio state championship. Although he came in second, the race was a turning point and he was hired as a parts sales representative for the Stearns bicycle factory, where he met his future wife, Beatrice Lovetta Oatis; they married in 1896.[5] By 1896, he was paid by Stearns in Syracuse, New York, to race on its amateur team.[4]

Auto racer

Oldfield was lent a gasoline-powered bicycle to race at Salt Lake City, which led to a meeting with Henry Ford, who had readied two automobiles for racing, and he asked Oldfield if he would like to test one at Ford's Grosse Pointe track. Oldfield agreed and traveled to Michigan for the trial, but neither car started. Despite the fact that Oldfield had never even driven an automobile, he and fellow racing cyclist Tom Cooper purchased both test vehicles when Ford offered to sell them for $800. One of them was the famous "No. 999" that debuted in October 1902 at the Manufacturer's Challenge Cup. Today it is displayed at the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village.

Oldfield agreed to drive against the current champion, Alexander Winton. Oldfield was rumored to have learned how to operate the controls of that car the morning of the event.[6] Oldfield won by a half mile in the five mile (8 km) race. He slid through the corners like a motorcycle racer did instead of braking. It was a great victory for Ford and led both Oldfield and Ford to become household names.

John Wilkinson, who designed an air-cooled engine for Franklin Automobile Company and was their chief engineer, raced against Oldfield in 1902, winning the state 5 miles (8.0 km) championship in the record time of 6:54:06.[7]

On June 20, 1903, at the Indiana State Fairgrounds, Oldfield became the first driver to run a mile track in one minute flat or 60 miles per hour (97 km/h).[8] Two months later, he drove one mile in 55.8 seconds at the Empire City Race Track in Yonkers, New York.[9] Winton hired Oldfield and agreed to supply free cars. Oldfield, his manager Ernest Moross, and agent Will Pickens traveled throughout the United States in a series of timed runs and match races, and he earned a reputation as a showman. He frequently raced in three event matches; in one, he won the first part by a nose, lost the second, before he won the third. Oldfield raced well at the Indianapolis Speedway in 1909 in a Mercedes.[10]

He bought a Benz, and raised his speed in 1910 to 70.159 mph (112.910 km/h) driving the "Blitzen Benz". Later in 1910 he drove to 131.25 mph (211.23 km/h). At Daytona Beach, Florida, on March 16, 1910, in his "Blitzen Benz", he set the world speed record, driving 131.724 mph, for which he earned the nickname “speed king”. In November 1914 he won the Los Angeles-to-Phoenix Cactus Derby Race; the victor's medal proclaimed him “Master Driver of the World”. On May 28, 1916, he became the first person to lap the Indianapolis Speedway at more than 100 mph in the front wheel drive Christie Racer designed by John Walter Christie. He used the Blitzen Benz to break the existing mile, two-mile, and kilometer records at the Daytona Beach Road Course at Ormond, Florida. He was able to charge $4,000 for every appearance afterwards.[4]

Suspension and later career

Oldfield was suspended by the American Automobile Association (AAA) for his "outlaw" racing and was unable to race at sanctioned events for much of his career. Speed records, match races, and exhibitions made up most of his career.

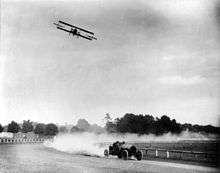

In 1914, his agent Will Pickens staged a "Championship of the Universe", pitting Oldfield against another one of his clients, the aviator Lincoln Beachey. Oldfield raced his Fiat car against Beachey's biplanes in at least 35 matches, barnstorming the country, "playing to more remote areas at county fair horse tracks". The Championship was "extremely successful", and both Oldfield and Beachey earned more than $250,000.[11]

He was reinstated by the AAA and competed in the 1914 and 1916 Indianapolis 500, finishing fifth in each attempt but becoming the first person to run a 100-mile-per-hour lap. His 1914 Indy finish was in an Indianapolis-built Stutz, making him the highest-finishing driver in an American car in a race dominated by Europeans.

Oldfield used the same car in his victory at the Los Angeles to Phoenix off-road race in November 1914. Oldfield also finished second in two major road races that year, the Vanderbilt Cup and the Corona 300. In 1915 he won the Venice, California 300 road race.

In June 1917 he used his Golden Submarine to beat fellow racing legend Ralph DePalma in a series of 10- to 25-mile (40 km) match races at Milwaukee. He retired from racing in 1918, but continued to tour and make movies. In what was his last attempt at racing, in 1932 he tried to re-enter speed racing with a new car design, but was unable to find any supporters.[13]

Oldfield died on October 4, 1946, of a heart attack. He was buried in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.[2]

Outside of racing

Performances

He starred in the Broadway musical The Vanderbilt Cup (1906) for ten weeks. His movie career included the silent film Barney Oldfield's Race for a Life (1913), where he raced against a train to rescue a heroine tied to the train tracks. He was also featured in The First Auto (1927) as an early pioneer of automotive history. He was a technical advisor for the Vanderbilt Cup sequence in the feature film Back Street (1941). He starred as himself in a racing film titled The Blonde Comet, the story of a young woman trying to achieve success as a racecar driver.

Racing safety

Bob Burman, one of Oldfield's rivals and closest friends, was killed in a wreck during a race in Corona, California. This led Oldfield and Harry Arminius Miller, who developed and built carburetors and was one of the most famous engine builders, to create a racecar that was not only fast and durable, but would also protect the driver in the event of an accident. They built a racecar with a roll cage inside a streamlined driver's compartment that completely enclosed the driver called the "Golden Submarine".

Business ventures

Oldfield helped fellow racer Carl G. Fisher found the Fisher Automobile Company in Indianapolis, thought to be the first automobile dealership in the United States.[14]

He also developed the Oldfield tire for Firestone. In its slogan, Firestone touted that Oldfield had said "Firestone Tires are my only life insurance".[15] In 1924, the Kimball Truck Co. of Los Angeles built the only 1924 Oldfield.[16]

Awards and recognition

The Oakshade Raceway in Wauseon, Ohio, Oldfield's birthplace, holds an annual race in his memory. His accomplishments led to the expression "Who do you think you are? Barney Oldfield?"

- In 1953, Oldfield was one of the first ten pioneers of auto racing enshrined in Auto Racing's Hall of Fame.[17]

- In 1990, he was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame.

- He was inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in the inaugural 1989 class as the at-large representative.

- He was named to the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame in 1990.

- He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1946.[18]

In Popular Culture

I Love Lucy episode "Lucy Learns to Drive" (Season 4): Ethel remarks "Oh, pardon me, Barney Oldfield."

Indy 500 results

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ "Barney Oldfield: American race–car driver". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Barney Oldfield, Ex-Racer, Is Dead. Pioneer Auto Driver Was First to Travel a Mile a Minute. Retired From Track in 1918. Daredevil of His Day Steered By Handles. Set Mark in Florida". New York Times. October 5, 1946.

- ↑ Michael Kernan (May 1998). "Wow! A Mile a Minute!". Smithsonian magazine.

- 1 2 3 "Barney Oldfield", International Motorsports Hall of Fame, 1990

- ↑ Barney Oldfield. The Gale Group. 2004. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Barney Oldfield", University of Virginia, Retrieved January 23, 2008

- ↑ "Local Autos Once Sold Widely". Syracuse Journal. March 20, 1939.

- ↑ "The First Mile-A-Minute Track Lap". Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Barney Oldfield", Rumbledrome

- ↑ Marshall Burchard (1975). Auto Racing Highlights. Garrard Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0811666732.

- ↑ Mark Dill. "Barney Oldfield and Lincoln Beachey". First Super Speedway. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ Donovan, Henry. "Chicago Eagle". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "Six Miles Per Minute Seen By Master Driver" Popular Mechanics, August 1932

- ↑ http://www.lostindiana.net/html/crown_hill__fisher.html

- ↑ "Barney Oldfield", Ohio History Central, July 1, 2005

- ↑ Old Cars, August 8, 1978. Motor West, June 1, 1924. Long Beach Press, 1924. Long Beach Telegram, 1924.

- ↑ The Detroit Free Press. February 19, 1953.

- ↑ "Ten pioneers are named to automotive Hall of Fame". Toledo Blade. Toledo, Ohio. May 1, 1946. p. 10. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

Further reading

- William F. Nolan, Barney Oldfield: The Life And Times Of America's Legendary Speed King; ISBN 978-1-888978-12-4

- International Motorsports Hall of Fame Biography

- "Barney Oldfield Biography"

- Beachey's aircraft vs. Oldfield's car

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barney Oldfield. |

- Barney Oldfield driver statistics at Racing-Reference

- Barney Oldfield & Ford - History & Photos

- Barney Oldfield (I) at the Internet Movie Database

- Exhibit on Barney Oldfield

- Barney Oldfield Speedway at Great America theme parks