Astures

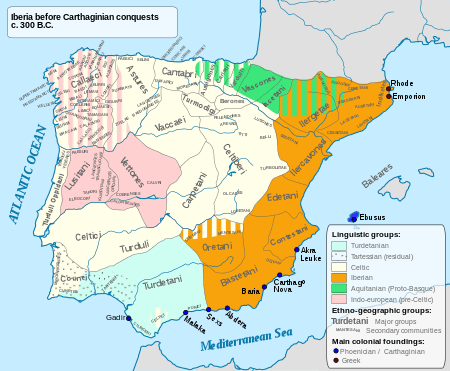

The Astures or Asturs, also named Astyrs,[1][2] were the Hispano-Celtic[3][4] inhabitants of the northwest area of Hispania that now comprises almost the entire modern autonomous community of Asturias, the modern province of León, and the northern part of the modern province of Zamora (all in Spain), and east of Trás os Montes in Portugal. They were a horse-riding highland cattle-raising people who lived in circular huts of stone drywall construction.[5] The Albiones were a major tribe from western Asturias.[6] Isidore of Seville[7] gave an etymology as coming from a river Asturia, identified by David Magie with the Órbigo in the plain of León, by others the modern Esla.

Location

The Asturian homeland encompassed the modern autonomous community of Asturias and the León, eastern Lugo, Orense, and northern Zamora provinces, along with the northeastern tip of the Portuguese region of Trás-os-Montes. Here they held the towns of Lancia (Villasabariego – León), Asturica (Astorga – León), Mons Medullius (Las Medulas? – León), Bergidum (Cacabelos, near Villafranca del Bierzo – León), Bedunia (Castro de Cebrones – León), Aliga (Alixa? – León), Curunda (Castro de Avelãs, Trás-os-Montes), Lucus Asturum (Lugo de Llanera – Asturias), Brigaetium (Benavente – Zamora), and Nemetobriga (Puebla de Trives – Orense), which was the religious center.

Origins

The Astures may have been part of the early Hallstatt expansion that left the Bavarian-Bohemian homeland and migrated into Gaul, some continuing over the mountains into Spain and Portugal.[5] By the 6th century BC, they occupied castros (hillforts), such as Coanna and Mohias near Navia on the coast of the Bay of Biscay.[5] From the Roman point-of-view, expressed in the brief remarks of the historians Florus, epitomising Livy, and Orosius , the Astures were divided into two factions, following the natural division made by the alpine karst mountains of the Picos de Europa range: the Transmontani (located in the modern Asturias, "beyond"— that is, north of— the Picos de Europa) and Cismontani (located on the "near" side, in the modern area of León). The Transmontani, placed between the Navia River and the central massif of the Picos de Europa, comprised the Cabarci, Iburri, Luggones, Paesici, Paenii, Saelini, Vinciani, Viromenici, Brigaentini and Baedunienses; the Cismontani included the Amaci, Cabruagenigi, Lancienses, Lougei, Tiburi, Orniaci, Superatii, Gigurri, Zoelae and Susarri (which dwelled around Asturica Augusta, in the Astura river valley, and was the main Astur town in Roman times). Prior to the Roman conquest in the late 1st century BC, they were united into a tribal federation with the mountain-top citadel of Asturica (Astorga) as their capital.

Culture

Recent epigraphic studies suggest that they spoke a ‘Q-Celtic’ language akin to the neighbouring Gallaeci Lucenses and Braccarenses (see Gallaecia).[8] Although the Celtic language was lost during the Low Middle Ages it still endures in many names of villages and geographical features, mostly associated to Celtic deities: the parish of Taranes and the villages of Tereñes, Táranu, Tarañu and Torañu related to the god Taranis, the parish of Lugones related to the god Lugh or the parish of Beleño related to the god Belenus, just to name a few.

According to classic authors, their family structure was matrilineal, whereby the woman inherits the ownership of property. The Astures lived in hill forts, established in strategic areas and built with round walls in today's Asturias and the mountainous areas of León, and with rectangular walls in flatter areas, similarly to their fellow Galicians. Their warrior class consisted of men and women and both sexes were considered fierce fighters.[5]

Religion

Most of their tribes, like the Lugones, worshipped the Celtic god Lugh, and references to other Celtic deities like Taranis or Belenos still remain in the toponomy of the places inhabited by the Astures. They may have venerated the deity Busgosu.[5]

Way of life

_01.jpg)

The Astures were vigorous hunter-gatherer highlanders who raided Roman outposts in the lowlands; a reputation enhanced by ancient authors, such as Florus ("Duae validissmae gentes, Cantabriae et Astures, immunes imperii agitabant")[9] and Paulus Orosius ("duas fortissimas Hispaniae gentes"),[10] but archeological evidence confirms that they also engaged in stock-raising in mountain pastures, complemented by subsistence farming on the slopes and in the lower valleys. They mostly reared sheep, goats, a few oxen and a local breed of mountain horse famed in Antiquity, the Asturcon, which still exists today. According to Pliny the Elder,[11] these were small-stature saddle horses, slightly larger than ponies, of graceful walk and very fast, being trained for both hunting and mountain warfare.

During a large part of the year they used acorns as a staple food source, drying and powdering them and using the flour for a type of easily preserved bread; from their few sown fields that they had during the pre-Roman period, they harvested barley from which they produced beer (Zythos),[12] as well as wheat and flax. Due to the scarcity of their agricultural production, as well as their strong war-like character, they made frequent incursions into the lands of the Vaccaei, who had a much more developed agriculture. Lucan calls them "Pale seekers after gold" ("Asturii scrutator pallidus auri").[13]

History

The Astures entered the historical record in the late 3rd century BC, being listed amongst the Spanish mercenaries of Hasdrubal Barca’s army at the battle of Metaurus River in 207 BC.[14][15] After the 2nd Punic War, their history is less clear. Rarely mentioned in the sources regarding the Lusitanian, Celtiberian or Roman Civil Wars of the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, they re-emerged from a relative obscurity just prior to the outbreak of the first Astur-Cantabrian war in the late 1st century BC.[16]

Led by the ex-mercenary General Gausón, the Astures joined forces with the Cantabri in an effort to forestall Emperor Augustus’ all-out offensive to conquer the whole of the Iberian northwest, even backing an unsuccessful Vaccaei revolt in 29 BC.[9][17][18] The Campaign against the Astures and Cantabri tribes proved so difficult that it required the presence of the emperor himself to bolster the failing courage of the seven legions and one naval squadron involved.[5] The first Roman campaign against the Astures (the Bellum Asturicum), which commenced in the spring of 26 BC, was successfully concluded in 25 BC with the ceremonial surrender of Mons Medullus to Augustus in person, allowing the latter to return to Rome and ostentatiously close the gates of the temple of Janus that same year.[19] The reduction of the remaining Asture holdouts was entrusted to Publius Carisius, the Legate of Lusitania, who, after managing to trap the Asturian General Gauson and the remnants of his troops at the hillfort of Lancia, subsequently forced them to surrender when he threatened to set fire to the town.[20] The Astures were subdued by the Romans but were never fully conquered, and their tribal way of life changed very little.[5]

As far as the official Roman history was concerned, the fall of this last redoubt marked the conclusion of the conquest of the Asturian lands, which henceforth were included alongside Gallaecia and Cantabria into the new Transduriana Province. This was followed by the establishment of military garrisons at Castra Legio VII Gemina (León) and Petavonium (Rosinos de Vidriales – Zamora), along with colonies at Asturica Augusta (Astorga) and Lucus Asturum.

In spite of the harsh pacification policies implemented by Augustus, the Asturian country remained an unstable region subjected to sporadic revolts – often carried out in collusion with the Cantabri – and persistent guerrilla activity that kept the Roman occupation forces busy until the mid-1st century AD. New risings occurred in 24–22 BC (the 2nd Astur-Cantabrian War), in 20–18 BC (3rd Astur-Cantabrian ‘War’) – sparked off by runaway Cantabrian slaves returning from Gaul[21] – both of which were brutally quashed by General Marcus Vispanius Agrippa[22] and again in 16–13 BC when Augustus crushed the last joint Astur-Cantabrian rebellion.

Romanization

Aggregated to the Hispania Tarraconensis province, the assimilation of the Asturian region into the Roman world was a slow and hazardous process, with its partially romanized people retaining the Celtic language, religion and much of their ancient culture throughout the Roman Imperial period. This included their martial traditions, which enabled them to provide the Roman Army with auxiliary cavalry units (Alae), who participated in Emperor Claudius’ invasion of Britain in AD 43–60. However, ephigraphic evidence in the form of an inscribed votive stele dedicated by a Primpilus Centurio of Legio VI Victrix decorated for bravery in action[23] confirms that the Astures staged a revolt in AD 54, prompting another vicious guerrilla war – unrecorded by the ancient sources – that lasted for fourteen years but the situation was finally calm around AD 68. Incredibly, they even enjoyed a brief revival during the Germanic invasions of the late 4th century AD, resisting Suevi and Visigoth raids throughout the 5th Century AD, only to be ultimately defeated and absorbed into the Visigothic Kingdom by the Visigothic King Sesibut in the early 6th Century AD. However in practice it was not so and the Astures continued to rebel and King Wamba had to send an expedition to Asturian lands only twenty years before the Muslim invasion of the peninsula and the fall of the Visigothic kingdom.

Legacy

At a later date, in the beginning of the Reconquista period in the early Middle Ages, their name was preserved in the medieval Kingdom of Asturias and in the modern town of Astorga, León, whose designation still reflects its early Roman name of Asturica Augusta, the "Augustan settlement of the Astures".

See also

- Leonese people

- Asturian people

- Astur-Cantabrian Wars

- Castro culture

- Gallaecia

- Eonavian

- Gausón

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

- Leonese language

Notes

- ↑ Silius Italicus, Punica, III, 325.

- ↑ Martino, Roma contra Cantabros y Astures – Nueva lectura de las fuentes, p. 18, footnote 15.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 481.

- ↑ Cólera, Carlos Jordán (16 March 2007). "The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula:Celtiberian" (PDF). e-Keltoi. 6: 749–750. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mountain, Harry (1997). The Celtic Encyclopedia Volume I. uPublish.com. pp. 130, 131. ISBN 1-58112-890-8.

- ↑ Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture : A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CIO. pp. 789, 790. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ Isidore of Seville, Etymologies, IX: 2, 112, noted by David Magie, "Augustus' War in Spain (26-25 B.C.)" Classical Philology 15.4 (October 1920:323–339) p.336 note 3.

- ↑ Cunliffe, The Celts – A Very Short Introduction (2003), p. 54.

- 1 2 Florus, Epitomae Historiae Romanae, II, 33.

- ↑ Paulus Orosius, Historiarum adversus Paganus, VI, 21.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, 7, 166.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographikon, III, 3, 7.

- ↑ Lucan, Pharsalia, IV, 298.

- ↑ Livy, Ad Urbe Condita, 27: 43–49.

- ↑ Polybius, Istorion, 11: 1–3.

- ↑ David Magie in Classical Philology 1920 gives the pertinent passages in Florus and Orosius and critically assesses and corrects the inconsistent topography of the sources.

- ↑ Paulus Orosius, Historiarum adversus Paganus, VI, 24.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Romaiké Istoria, 51, 20.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Romaiké Istoria, 53: 26.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Romaiké Istoria, 53: 25, 8; attributed the victory in error to Titus Carasius, father of Publius Carasius (Magie 1920:338 note 4).

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Romaiké Istoria, 54: 11, 1.

- ↑ Magie 1920:339.

- ↑ CIL XI 395, from Ariminum; cf: B. Dobson, Die Primpilares (Beihefte der Bonner Jahrbücher XXXVII), Köln 1978, pp. 198–200.

Sources

- Almagro-Gorbea, Martín, Les Celtes dans la péninsule Ibérique, in Les Celtes, Éditions Stock, Paris (1997) ISBN 2-234-04844-3

- Alvarado, Alberto Lorrio J., Los Celtíberos, Editorial Complutense, Alicante (1997) ISBN 84-7908-335-2

- Cunliffe, Barry, The Celts – A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2003) ISBN 0-19-280418-9

- Duque, Ángel Montenegro et alli, Historia de España 2 – colonizaciones y formacion de los pueblos prerromanos, Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1013-3

- Martino, Eutimio, Roma contra Cantabros y Astures – Nueva lectura de las fuentes, Breviarios de la Calle del Pez n. º 33, Diputación provincial de León/Editorial Eal Terrae, Santander (1982) ISBN 84-87081-93-2

- Motoza, Francisco Burillo, Los Celtíberos – Etnias y Estados, Crítica, Grijalbo Mondadori, S.A., Barcelona (1998, revised edition 2007) ISBN 84-7423-891-9

- Jiménez, Ana Bernardo (dirección), Astures – pueblos y culturas en la frontera del Imperio Romano, Asociación Astures, Gran Enciclopedia Asturiana, Gijón (1995) ISBN 84-7286-339-5, 84-7286-342-5

- Koch, John T.(ed.), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO Inc., Santa Barbara, California (2006) ISBN 1-85109-440-7, 1-85109-445-8

Further reading

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis & Gardes, Philippe, Entre celtas e íberos, Real Academia de la Historia/Fundación Casa de Velázquez, Madrid (2001) ISBNs 978-84-89512-82-5, 978-84-95555-10-6

- Heinrich Dyck, Ludwig, The Roman Barbarian Wars: The Era of Roman Conquest, Author Solutions (2011) ISBNs 1426981821, 9781426981821

- Kruta, Venceslas, Les Celtes, Histoire et Dictionnaire: Des origines à la Romanization et au Christinisme, Èditions Robert Laffont, Paris (2000) ISBN 2-7028-6261-6

- Martín Almagro Gorbea, José María Blázquez Martínez, Michel Reddé, Joaquín González Echegaray, José Luis Ramírez Sádaba, and Eduardo José Peralta Labrador (coord.), Las Guerras Cántabras, Fundación Marcelino Botín, Santander (1999) ISBN 84-87678-81-5

- Varga, Daniel, The Roman Wars in Spain: The Military Confrontation with Guerrilla Warfare, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2015) ISBN 978-1-47382-781-3

- Zapatero, Gonzalo Ruiz et alli, Los Celtas: Hispania y Europa, dirigido por Martín Almagro-Gorbea, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Editorial ACTAS, S.l., Madrid (1993) ISBNs 8487863205, 9788487863202