Anthony Casso

| Anthony Casso | |

|---|---|

|

NYPD mugshot of Casso 12/20/1972 | |

| Born |

Anthony Salvatore Casso May 24, 1940 Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Nationality | Italian-American |

| Other names | Gaspipe |

| Criminal penalty | 455 years in prison |

| Spouse(s) | Lillian Delduca (1968–2005) |

| Children | 2 |

| Allegiance | Lucchese crime family |

| Conviction(s) | March 15, 1994 (pleaded guilty) |

Anthony Salvatore "Gaspipe" Casso (born May 21, 1940 in Brooklyn, New York City) is an Italian-American mobster and former underboss of the Lucchese crime family. During his career in organized crime, Casso was regarded as a "homicidal maniac" in the American Mafia and single handedly killing over 40 to 50 people, and ordering as many as 100 or more murders.[1] Former Lucchese captain and government witness Anthony Accetturo once said of Casso, "all he wanted to do is kill, kill, get what you can, even if you didn't earn it."[2]

In interviews and on the witness stand, Casso has confessed involvement in the murders of Frank DeCicco, Roy DeMeo, and Vladimir Reznikov. Casso has also admitted to several attempts to murder Gambino crime family boss John Gotti.

Following his arrest in 1993, Casso became one of the highest-ranking members of the Mafia to turn informer. In 1998, however, the United States Federal Government rescinded Casso's plea agreement and dropped him from the witness protection program. Later that year, a federal judge sentenced him to 455 years in prison.

Casso's life was documented in the 2008 true crime book, Gaspipe: Confessions of a Mafia Boss, by Philip Carlo.

Early life

Born in South Brooklyn, Casso was the youngest of the three children of Michael and Margaret Casso (née Cucceullo). Each of Casso's grandparents had emigrated from Campania, Italy, during the 1890s. His godfather was Salvatore Callinbrano, a made man and captain in the Genovese crime family, who maintained a powerful influence on the Brooklyn docks. Casso dropped out of school at 16 and got a job with his father as a longshoreman. As a young boy, Casso became a crack shot, firing pistols at targets on a rooftop which he and his friends used as a shooting range. Casso also made money shooting predatory hawks for pigeon tenders. Casso stood at 5'6 and weighed 185 pounds.

Casso was a violent youth and member of the infamous 1950s gang, the South Brooklyn Boys.[3][4] In 1958, he was arrested after a "rumble" against Irish-American gangsters. Casso later told Philip Carlo that his father visited him at the police station and tried in vain to scare his son straight.

Casso soon caught the eye of Christopher "Christie Tick" Furnari, the capo of one of the most powerful crews in the Lucchese family, the "19th Hole Crew." Casso started his career in organized crime as a loanshark. As a protégé of Furnari, Casso was also involved in gambling and drug dealing, in addition to loansharking. He was arrested for attempted murder in 1961, but was acquitted when the alleged victim refused to identify him. He would not see the inside of a cell again for over 30 years.

Over the years, there have been various stories of how Casso got the nickname "Gaspipe." Even though Anthony detested the nickname, it stuck to him for life and though few would say it to his face, he allowed some close friends to call him "Gas".

During the 1970s, Casso was one of a string of Mafia associates who were suspected of cooperating with the Federal government. In 1974, at age 32, Casso became a made man, or full member, of the Lucchese family. Casso was assigned to Vincent "Vinnie Beans" Foceri's crew that operated from 116th Street in Manhattan and from Fourteenth avenue in Brooklyn.[5][6]

Shortly after becoming made, Casso became close to another rising star in the family, Vic Amuso. It was the start of a partnership that would last for two decades. They committed scores of crimes, including drug trafficking, burglary and the murders of informants. When Furnari became the Lucchese consigliere, he asked Casso to take over the 19th Hole Crew. However, Casso declined, suggesting that Amuso be promoted instead. Casso opted to become Furnari's aide; a consigliere is allowed to have one soldier work for him directly.

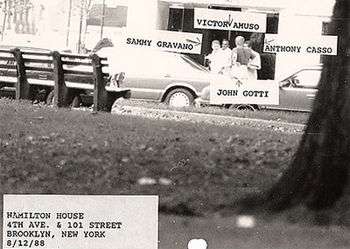

In December 1985, Casso was approached by Gambino capo Frank DeCicco regarding a planned coup in his own family.[7] John Gotti, another Gambino capo whose crew had been implicated in drug deals, was planning to kill his boss Paul Castellano and take over the Gambino family, and was looking for support among the acting bosses-in-waiting of the families affected by the Commission case.[8] According to Sammy Gravano, another of Gotti's co-conspirators who would later turn state's evidence, Casso offered the conspirators his support.[9] Casso himself would claim he tried to talk DeCicco out of participating in the coup, warning him that, without official sanction for the Commission, all the participants would be murdered in revenge.[7] The hit went ahead regardless on December 16;[8] Casso would later denounce Gotti's actions to biographer Philip Carlo as "the beginning of the end of our thing."[7]

As Casso had warned, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo and Genovese boss Vincent Gigante decided to kill Gotti and DeCicco, his new underboss, in revenge. Amuso and Casso were chosen to handle the assassinations, and were instructed to use a bomb to try and shift suspicion to Sicilian mafiosi or Zips based in the United States. While American mafiosi have long been (officially) banned from using bombs due to the risk of collateral damage, Sicilian mafiosi were notorious for blowing up their targets. Amuso and Casso made one attempt on the lives of Gotti and DeCicco, planting a bomb in DeCicco's car when the two were scheduled to visit a social club on April 13, 1986. Gotti cancelled at the last minute, however, and the bomb instead only killed DeCicco and injured the passenger they had mistaken for Gotti.[9]

Big Money

In the fall of 1986, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo sensed that the Commission Trial would result in a guilty verdict that would ensure the entire Lucchese leadership would die in prison. Wanting to maintain the family's half-century tradition of a seamless transfer of power, Corallo endorsed Casso as his successor. However, Casso turned it down and instead suggested that Amuso become new boss.

Amuso formally took over the family in 1987, and Casso succeeded Furnari as consigliere. Amuso named him underboss in 1989 after Mariano Macaluso retired. However, Casso wielded as much influence as Amuso. According to federal and state investigators, Amuso attended to policy issues and representing the family at Commission meetings, leaving day-to-day control of the family to Casso.

During this time, Casso maintained a glamorous lifestyle, wearing expensive clothes and jewelry (including a diamond ring worth $500,000), running restaurant tabs up to thousands of dollars, owning a mansion in an exclusive Brooklyn neighborhood and going on huge spending sprees. While at the top of the Lucchese family, Amuso and Casso shared huge profits from their family's illegal activities. These profits included: $15,000 to $20,000 a month from extorting Long Island carting companies; $75,000 a month in kickbacks from eight air freight carriers that guaranteed them labor peace and no union benefits for their workers; $20,000 a week in profits from illegal video gaming machines; and $245,000 annually from a major concrete supplier, the Quadrozzi Concrete Company."[10] Amuso and Casso also split more than $200,000 per year from the Garment District rackets, as well as a cut of all the crimes committed by the family's soldiers.

Paying dues

In one instance, Casso and Amuso split $800,000 from the Colombo crime family for Casso's aid in helping them rob steel from a construction site at the West Side Highway in Manhattan. In another instance, the two bosses received $600,000 from the Gambino crime family for allowing them to take over a Lucchese-protected contractor for a housing complex project in Coney Island, Brooklyn.

Casso also controlled Greek-American gangster George Kalikatas, who gave Casso $683,000 in 1990 to operate a loan sharking and gambling operation in Astoria, Queens.

Eastern European connections

Anthony Casso had a close alliance with Ukrainian mob boss Marat Balagula, who operated a multibillion-dollar gasoline bootlegging scam in Brighton Beach. Balagula, a Soviet Jewish refugee from Odessa, had arrived in the United States under the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. After Colombo captain Michael Franzese began shaking down his crew, Balagula approached Lucchese consiglieri Christopher Furnari and asked for a sit-down at Brooklyn's 19th Hole social club. According to Casso, Furnari declared,

"Here there's enough for everybody to be happy... to leave the table satisfied. What we must avoid is trouble between us and the other families. I propose to make a deal with the others so there's no bad blood.... Meanwhile, we will send word out that from now on you and your people are with the Lucchese family. No one will bother you. If anyone does bother you, come to us and Anthony will take care of it."[11]

Street tax from Balagula's organization was not only strategically shared, but also became the Five Families' biggest moneymaker after narcotics trafficking.

According to Philip Carlo,

"It didn't take long for word on the street to reach the Russian underworld: Marat Balagula was paying off the Italians; Balagula was a punk; Balagula had no balls. Balagula's days were numbered. This, of course, was the beginning of serious trouble. Balagula did in fact have balls – he was a ruthless killer when necessary – but he also was a smart diplomatic administrator and he knew that the combined, concerted force of the Italian crime families would quickly wipe the newly arrived Russian competition off the proverbial map."[12]

Shortly afterward, Balagula's rival, a fellow Russian immigrant named Vladimir Reznikov, drove up to Balagula's offices in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. Sitting in his car, Reznikov opened fire on the office building with an AK-47. One of Balagula's close associates was killed and several secretaries were wounded.[13]

Then, on June 12, 1986, Reznikov entered the Rasputin nightclub in Brighton Beach. Reznikov placed a 9mm Beretta against Balagula's head and demanded $600,000 as the price of not pulling the trigger. He also demanded a percentage of everything Balagula was involved in. After Balagula promised to get the money, Reznikov snarled, "Fuck with me and you're dead – you and your whole fucking family; I swear I'll fuck and kill your wife as you watch – you understand?"[14]

Shortly after Reznikov left, Balagula suffered a massive heart attack. He insisted, however on being treated at his home in Brighton Beach, where he felt it would be harder for Reznikov to kill him. When Anthony Casso arrived, he listened to Balagula's story and seethed with fury. Casso later told his biographer Philip Carlo that, to his mind, Reznikov had just spat in the face of the entire Cosa Nostra. Casso responded, "Send word to Vladimir that you have his money, that he should come to the club tomorrow. We'll take care of the rest."[15] Balagula responded, "You're sure? This is an animal. It was him that used a machine gun in the office."[16] Casso responded, "Don't concern yourself. I promise we'll take care of him... Okay?" Casso then requested a photograph of Reznikov and a description of his car.[15]

The following day, Reznikov returned to the Rasputin nightclub to pick up his money. Upon realizing that Balagula wasn't there, Reznikov launched into a barrage of profanity and stormed back to the parking lot. There, Reznikov was shot dead by DeMeo crew veteran Joseph Testa. Testa then jumped into a car driven by Anthony Senter and left Brighton Beach. According to Casso, "After that, Marat didn't have any problems with other Russians."[17]

Fugitive boss

On July 29, 1991, due to a tipoff from an unidentified Lucchese insider, Victor Amuso was arrested, further securing Casso as the de facto boss of the family.[18][19] In Ernest Volkman's book Gangbusters he identified Casso as the most likely source for the leak, noting only a few people were privy to the boss' location and suggesting Casso wanted complete control of the family.[20] This theory is contradicted, however, by Casso's biographer Philip Carlo. According to Carlo, Casso had no desire to be boss of the Lucchese family and attempted to arrange for Amuso's escape from federal custody after his arrest. To the great disappointment of Casso and the Lucchese captains, Amuso refused to leave prison out of fear for his life. As a result, the Lucchese captains asked Casso to take over as acting boss. Casso reluctantly accepted.

While evading authorities for over three years, Casso maintained control over the Lucchese family. In the process, he ordered 11 mob slayings as well as plotting with Genovese leader Vincent "the Chin" Gigante to murder John Gotti. Casso and Gigante were deeply disgusted that Gotti had murdered Paul Castellano without the sanction of the Mafia's Commission. All attempts on Gotti's life were stymied, however, by the constant presence of news reporters around the Gambino boss.

In early 1991, Amuso and Casso ordered the murder of capo Peter Chiodo, a fellow windows case defendant who had pleaded guilty without the administrations' approval. Chiodo barely survived the assassination attempt and subsequently agreed to turn state's evidence.[21] In September that year acting boss Al D'Arco, convinced Casso had marked him for death following his failure to kill Chiodo, also surrendered and agreed to testify. Both of these defections opened the door for new murder indictments against Amuso and Casso.[19]

In another incident toward the year of 1993, Casso used the Brooklyn faction-leaders George Zappola, Frank "Bones" Papagni as well as the family Consigliere, Frank "Big Frank" Lastortino, to kill former Lucchese Underboss and Bronx faction leader Stephen "Wonderboy" Crea. However, due to the massive indictments at the time, all members of the plot were eventually incarcerated on various charges, including Casso, who was arrested at a mistress's home in Mount Olive, New Jersey, on January 19, 1993.[22]

Informant

Casso was held at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, New York City pending trial. Facing charges that would have all but assured he would die in prison, he began making escape plans.[23] One plan almost succeeded when a bribed guard cleared him through security; Casso nearly walked out of jail, but was spotted by another guard and thwarted at the last minute.[24] Afterwards Casso began making plans for Lucchese members to find out what prison buses would be transporting him and arrange an ambush,[25] as well as assassinating the presiding judge Eugene Nickerson to buy himself more time.[24] However, all of this came undone in 1993 when Amuso not only stripped Casso of his title of underboss, but declared that all Lucchese mafiosi should consider him a pariah—in effect, banishing Casso from the family.[24] Amuso had long been suspicious of Casso's failure to use his law enforcement contacts to find out who betrayed him,[26] and finally concluded Casso did it himself to take control of the family.[24]

With D'Arco, Acceturo, and Chiodo due to be star witnesses against him, Casso offered become a federal witness just before his trial was due to begin. He finalized a deal at a hearing on March 1, 1994, where he pleaded guilty to all 72 counts he had been indicted on, now including 15 murders.[24][27]

Casso disclosed that two retired NYPD detectives had been on the Lucchese payroll. These detectives were later determined to be Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa, who committed eight of the eleven murders Casso had ordered. Carracappa and Eppolito had also given Casso information which led to many others as well, revealing the names of potential informants. They were subsequently found guilty on all charges and sentenced to life in prison. However, when Casso revealed that he also had an FBI agent on the payroll, prosecutors ordered him to keep quiet. Casso further enraged the federal government by accusing Gambino turncoat Sammy Gravano of committing multiple felonies which he had later denied on the witness stand.

Casso claimed to have sold large amounts of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana to Gravano over two decades. Once again, no one was interested. However, Casso was vindicated to some extent in 2000 when Gravano pleaded guilty to operating a massive narcotics ring, which included selling ecstasy to junior high children [28]

In 1997, Casso was thrown out of the Witness Protection Program. Prosecutors alleged numerous infractions, including bribing guards, assaulting other inmates and making "false statements" about federal witnesses Gravano and D'Arco. Casso's attorney tried to get Judge Frederic Block to overrule federal prosecutors in July 1998, but Block refused to do so.[29] Shortly afterward, Judge Block sentenced Casso to 455 years in prison without possibility of parole—the maximum sentence permitted under sentencing guidelines.[30]

Casso later told New York Times organized-crime reporter Selwyn Raab that, before turning informer, he was seriously considering a deal that would have allowed him the possibility of parole after 22 years. "I help them and I get life without parole," he said. "This is really a fuckin' joke."[31]

In a 2006 letter to Philip Carlo, Casso declared,

"I am truly regretful for my decision to cooperate with the Government. It was against all my beliefs and upbringing. I know for certain, had my father been alive, I would never have done so. I have disgraced my family heritage, lost the respect of my children and close friends, and most probably added to the sudden death of my wife and confidant for more than 35 years. I wish the clock could be turned back only to bring her back. I have never in my life informed on anyone. I have always hated rats and as strange as it may sound I still do. I surely hate myself, day after day. It would have definitely been different if the Government had honest witnesses from inception. I would have had a second chance to start a new life, and my wife Lillian would still be alive. It seems that the only people the Government awards freedom to are the ones who give prejudiced testimony to win convictions. 'The Truth Will Set You Free,' means nothing in the Federal courts. Even at this point in my life I consider myself to be a better man than most of the people on the streets these days."[32]

Incarceration

Anthony Casso began serving his sentence at the Supermax Prison in Florence, Colorado.

According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, in March 2009 Anthony Casso was transferred to the Federal Medical Center (FMC) at the Federal Correctional Complex, Butner in North Carolina for the treatment of prostate cancer.[33] However, by July 2009, he had been returned to ADX Florence.

By 2013, Casso had been transferred to the Federal Residential Reentry Management Office in Minneapolis, Minnesota.[34] This is not a prison facility, but rather is an administrative designation for inmates assigned to home confinement, "halfway houses", or state and county correctional facilities. As Casso is serving a life sentence, this almost certainly means that he is being housed at a Minnesota state prison. However, a search of the Minnesota Department of Corrections inmate database does not reveal anyone being held under his name, making it very likely he is being held under an alias.

Family

He married fellow South Brooklyn native Lillian Delduca on May 4, 1968.[35] They had a daughter and son. Despite knowing about his many infidelities, Lillian Casso continued to support her husband until her death in February, 2005.

In an interview with Carlo, Casso recalled,

"Most all men in my life, everyone I know, had girlfriends. It goes with the territory. Women are drawn to us, the power, the money, and we're drawn to them. But only in passing. Some guys treated their mistresses better than their wife, but that's a fuckin' outrage. No class. Only a cafone does that. I never loved any woman but Lillian. She and my family always came first."[36]

References

Notes

- ↑ Ackman, Dan (March 17, 2006). "Dispatches From a Mob Trial". Dispatches. Slate. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Raab, p. 507-509.

- ↑ Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires, by Selwyn Raab, (Page 470)

- ↑ The Brotherhoods: The True Story of Two Cops Who Murdered for the Mafia By Guy Lawson, (Page 147)

- ↑ Gaspipe, page 85-86.

- ↑ National Council on Crime and Delinquency – 1969 Volume 44. (Page 147) see Vincent Foceri

- 1 2 3 Carlo, pp. 134-136

- 1 2 Raab, pp. 371-375

- 1 2 Raab, pp. 473-475

- ↑ Selwyn Raab, Five Families

- ↑ Carlo 2008, p. 120

- ↑ Carlo 2008, p. 152

- ↑ Carlo (2008), page 152.

- ↑ Gaspipe, page 153.

- 1 2 Gaspipe, page 154.

- ↑ Carlo (2008), page 154.

- ↑ Robert I. Friedman, Rad Mafiya; How the Russian Mob has Invaded America, 200 Page 55.

- ↑ McQuiston, John (1991-07-30). "Fugitive In Mob Case Is Arrested". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- 1 2 Raab, pp. 499–501

- ↑ Volkman, p. 281

- ↑ Raab, pp. 496–498

- ↑ Raab, p. 511

- ↑ Lawson; Oldham, p. 257

- 1 2 3 4 5 Raab, pp. 512–514

- ↑ Lawson; Oldham, pp. 261-262

- ↑ Lawson; Oldham, p. 264

- ↑ Helen Peterson (July 1, 1998). "Wiseguy Won't Get Fed Aid On Sentence". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ↑ [Gaspipe- confessions of a mafia boss, Philip Carlo, 2008]

- ↑ Plea Deal Rescinded, Informer May Face Life by Selwyn Raab (July 1, 1998) New York Times

- ↑ Raab, p. 522

- ↑ Raab, p. 525.

- ↑ Carlo (2008), page 337.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Ralph (2009-02-21). "Mobster Makes Offer on French Connection Case". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ↑ Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator

- ↑ Philip Carlo, Gaspipe, page 46.

- ↑ Philip Carlo, "Gaspipe: Confessions of a Mafia Boss," pages 185-186.

Sources

- Kelly, Robert J. Encyclopedia of Organized Crime in the United States. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30653-2

- Capeci, Jerry, and Mustain, Gene. Gotti: Rise and Fall. Penguin Books Canada, Limited (1996)

- Lawson, Guy, and Oldham, William. The Brotherhoods, Pocket Books (2007) ISBN 1-4165-2338-3

- Carlo, Philip (2008). Gaspipe: Confessions of a Mafia Boss. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780061429842.

- Joseph D. Pistone, and Charles Brandt. Donnie Brasco: Unfinished Business, Running Press Book Publishers (2007) ISBN 978-0-7624-2707-9

- Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (2006 ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780312361815.

- Volkman, Ernest (1998). Gangbusters: The Destruction of America's Last Great Mafia Dynasty (1999 paperback ed.). New York: Avon Books. ISBN 0380732351.

External links

- Anthony Casso – Biography.com

- The Lucchese Family – TruTV Crime Library

- Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator: Anthony Casso (Life)

| Business positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mariano "Mac" Macaluso |

Lucchese crime family Underboss 1989-1993 |

Succeeded by Steven Crea |