Anglo-Dutch Wars

| ||||||||||

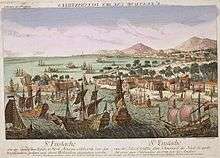

The Anglo-Dutch wars (Dutch: Engels–Nederlandse Oorlogen or Engelse Zeeoorlogen) were wars between England/Britain (the Commonwealth of England, the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) and the Dutch states (the Dutch Republic and the Batavian Republic). They were fought in the periods 1652-1674 and 1781-1810, for the control of trade routes and colonies. There were numerous naval battles, most of which were drawn.

Background

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, neither England nor the main maritime provinces of the Low Countries, Flanders and Holland, had been major European sea powers on par with the commerce driven sea powers such as Venice, Genoa, Portugal, Castile or Aragon. As the Age of Exploration stimulated trade, the Dutch and English—both influenced by mercantilism and centuries of commerce with the other state—were independently compelled to the need to look for colonies and wealth in the newly exposed New World. Led by the Dutch invention of the Joint Stock Company and spurred by rivalry with the Spanish Empire, the Dutch financed expeditions to the orient with stock subscriptions sold in the United Provinces and in London. Thanks to fisheries, the wool trade, and Baltic ships stores, the two regions had long standing relationships.

In the second-half of the 16th century, during the Wars of Religion between the fanatically-Catholic Habsburg Dynasty and the various (newly formed or converted) Protestant states each were embroiled in the greater Catholic versus Protestant conflicts, diplomatically, if not directly.

During these struggles, Elizabeth I of England built up a strong naval force, designed a harassment strategy to carry out long range privateering or piracy missions against the Spanish Empire's world wide interests, exemplified by the exploits of Francis Drake. These raids, financed by the Crown or high nobility, were initially immensely profitable—until the overhaul of Spain's naval and intelligence systems led to a series of costly failures.

Partly to provide a pretext for such hostilities against Spain, Elizabeth assisted the Dutch Revolt (1581) against the uber-Catholic Kingdom of Spain by signing the Treaty of Nonsuch in 1585 with the new Dutch state of the United Provinces. In the resulting naval actions of the Anglo-Spanish War, the Dutch played only a secondary role as they were fully occupied in fighting Habsburg armies and defending their frontiers at home from troops coming up the Spanish Road, and their coast from invasion attempts. The era's naval battles did not yet involve large numbers of purpose built warships, but instead relied upon converted merchant vessels, mostly Galleons and ocean-going caravels—armed cargo vessel classes dragooned into service to the state on which extra canon were mounted and whose man-power was augmented for boarding actions.

Around the turn of the 17th century Anglo-Spanish relations began to improve, resulting in the peace of 1604, ending most privateering actions. As was usual for the times, paltry funding by Parliament again lead to neglect of the Royal Navy. England had not yet built its self-image as a sea power whose seaborne trade fueled its economy and had to be protected. When the colony of Jamestown was founded in North America, it had the incentive of support from a joint-stock company, not the English crown or navy.

The unsuccessful Anglo-Spanish War of 1625 was only a temporary change in policy influenced by maneuvers of international politics. Gradually, as the English observed the accumulating wealth of the Dutch, covetous men of influence under the spell of the theories of mercantilism became focused on colonialism as a means of creating both personal and national wealth. In the process, parliamentarily governed England found a capitalistic need within parliament's reasoning's to develop and build naval capabilities of its own. These efforts also resulted in competition and frictions that often put the capitalistic energies of the two Protestant nations at odds; adding to the frictions between their competing views of religious orthodoxy.

In the same early-1600s period, the Dutch, continuing their conflict (Eighty Years' War) with the Habsburgs]], began to carry out long distance actions such as exploration expeditions, the founding of colonies in North America (1608), India, and Indonesia (Spice Islands) in addition to their continued great successes in privateering. With the many long voyages by Dutch East Indiamen, their society consequently built an officer class and institutional knowledge; skill sets and experience that later the English would have to duplicate and overcome. In 1628 Admiral Piet Heyn became the only commander to successfully capture a large Spanish treasure fleet. Thus, the Dutch replaced the Portuguese as the main European traders in Asia. News of the captures and success in the early stock markets however whetted the appetites of many an English capitalist.

The Dutch, taking over most of Portugal's trading posts in the East Indies, gained control over the hugely profitable trade in spices. This coincided with the enormous growth of the Dutch merchant fleet, made possible by the cheap mass production of the fluyt sailing ship types. Soon the Dutch had Europe's largest mercantile fleet, with more merchant ships than all other nations combined, and a dominant position in European (especially Baltic) trade. Though less spectacularly so, the Dutch navy also grew in power, for in the era, most naval warfare was still conducted by adding cannon to cargo ships—a strategy England would challenge and beat by introducing purpose built warships.

From January 1631 Charles I of England engaged in a number of secret agreements with Spain, directed against Dutch sea power. He also embarked on a major program of naval construction, enforcing ship money to build such prestige vessels as HMS Sovereign of the Seas. Charles's policy was not very successful, however. Fearful of endangering his good relations with the powerful Dutch stadtholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, his assistance to Spain was limited to allowing Habsburg troops on their way to Dunkirk to employ neutral English shipping; in 1636 and 1637 he made some halfhearted attempts to extort North Sea herring rights from Dutch fishermen until intervention by the Dutch navy put an end to such practices. In the new world, Dutch New Netherlands and Massachusetts Bay Colony contested the mid-Atlantic coast and most of Southern New England. When in 1639 a large Spanish transport fleet sought refuge in the English Downs moorage, Charles did not dare to protect it against a Dutch attack; the resulting Battle of the Downs undermined both Spanish sea power and Charles's already abysmal reputation.

Commencing soon thereafter, the English Civil War, severely weakened England's naval position for a time. Its navy was as internally divided as was the country as a whole; the Dutch, as superior on land as they were at sea, even took over much of England's maritime trade with its North American colonies. Between 1648 and 1651, however, the situation reversed completely. In 1648 the United Provinces concluded the Peace of Münster with Spain. Due to the division of powers in the Dutch Republic, the army and navy were the main base of power of the stadtholder, although the budget allocated to the military was set by the States General. With the war gone, the States General decided to decommission most of the Dutch army and navy. This led to conflict between the major Dutch cities and the new stadtholder, William II of Orange, bringing the Republic to the brink of civil war; the stadtholder's unexpected death in 1650 only added to the political tensions.

Meanwhile in the English civil war, Oliver Cromwell united his country into the Commonwealth of England and in a few years created a powerful navy, expanding the number of ships and greatly improving organisation and discipline positioning England to mount a global challenge to Dutch trade dominance.

The mood in England was rather belligerent towards the Dutch. This partly stemmed from old perceived slights: the Dutch were considered to have shown themselves ungrateful for the aid they had received against the Spanish by growing stronger than their former English protectors; they caught most of the herring off the English east coast; they had driven the English out of the East Indies, committing presumed atrocities such as the Amboyna Massacre while vociferously appealing to the principle of free trade to circumvent taxation in the English colonies. There were also new points of conflict: with the decline of Spanish power at the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648, the colonial possessions of Portugal (already in the midst of Portuguese Restoration War), and perhaps even of a beleaguered Spain, were up for grabs. The Dutch had after 1648 quickly replaced the English in their traditional Iberian trade. Cromwell feared the influence of the Orangist faction and English exiles in the Republic because the stadtholders had always supported the Stuarts; the Dutch abhorred the decapitation of Charles I.

Early in 1651 Cromwell tried to ease tensions by sending a delegation to The Hague proposing that the Dutch Republic join the Commonwealth and assist the English in conquering most of Spanish America for its extremely valuable resources. This barely veiled attempt to end Dutch sovereignty ended in war. The ruling peace faction in the States of Holland was unable to formulate an answer to the unexpected and far-reaching offer. The pro-Stuart Orangists incited mobs to harass the envoys. When the delegation returned, the English Parliament, feeling deeply offended by the Dutch attitude, decided to pursue a policy of confrontation.

First war (1652–1654)

The British had much the stronger Navy, with larger and more powerful warships. The Dutch had a much more efficient trading system, with more ships, lower freight rates, better financing, and a wider range in quality of manufactured goods to sell. However, Dutch ships were blocked by the Spanish from operations in most of southern Europe, giving the British an advantage there.[1]

To protect its position in North America, in October 1651 the English Parliament passed the first of the Navigation Acts, which mandated that all goods imported into England must be carried by English ships or vessels from the exporting countries, thus excluding (mostly Dutch) middlemen. This typical mercantilist measure as such did not hurt the Dutch much as the English trade was relatively unimportant to them, but it was used by the many pirates operating from British territory as an ideal pretext to legally take any Dutch ship they encountered. The Dutch responded to the growing intimidation by enlisting large numbers of armed merchantmen into their navy. The English, trying to revive an ancient right they perceived they had to be recognised as the 'lords of the seas', demanded that other ships strike their flags in salute to their ships, even in foreign ports. On 29 May 1652, Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp refused to show the respectful haste expected in lowering his flag to salute an encountered English fleet. This resulted in a skirmish, the Battle of Goodwin Sands, after which the Commonwealth declared war on 10 July.

After some inconclusive minor fights the English were successful in the first major battle, General at Sea Robert Blake defeating the Dutch Vice-Admiral Witte de With in the Battle of the Kentish Knock in October 1652. Believing that the war was all but over, the English divided their forces and in December were routed by the fleet of Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp at the Battle of Dungeness in the English Channel. The Dutch were also victorious in March 1653 at the Battle of Leghorn near Italy and had gained effective control of both the Mediterranean and the English Channel. Blake, recovering from an injury, rethought, together with George Monck, the whole system of naval tactics, and after the winter of 1653 used the line of battle, first to drive the Dutch navy out of the English Channel in the Battle of Portland and then out of the North Sea in the Battle of the Gabbard. The Dutch were unable to effectively resist as the States General of the Netherlands had not in time heeded the warnings of their admirals that much larger warships were needed. In the final Battle of Scheveningen on 10 August 1653 Tromp was killed, a blow to Dutch morale, but the English had to end their blockade of the Dutch coast. As both nations were by now exhausted and Cromwell had dissolved the warlike Rump Parliament, ongoing peace negotiations could be brought to fruition, albeit after many months of slow diplomatic exchanges.

The British captured about 1200 to 1500 Dutch merchant ships. The war ended on 5 April 1654 with the signing of the Treaty of Westminster (ratified by the States General on 8 May), but the commercial rivalry was not resolved, the English having failed to replace the Dutch as the world's dominant trade nation. The treaty contained a secret annex, the Act of Seclusion, forbidding the infant Prince William III of Orange from becoming stadtholder of the province of Holland, which would prove to be a future cause of discontent. In 1653 the Dutch had started a major naval expansion programme, building sixty larger vessels, partly closing the qualitative gap with the English fleet. Cromwell, having started the war against Spain without Dutch help, during his rule avoided a new conflict with the Republic, even though the Dutch in the same period defeated his Portuguese and Swedish allies.

Second war (1665–1667)

After the English Restoration in 1660, Charles II tried to serve his dynastic interests by attempting to make Prince William III of Orange, his nephew, stadtholder of the Republic, using some military pressure. This led to a surge of patriotism in England, the country being, as Samuel Pepys put it, "mad for war". King Charles promoted a series of anti-Dutch mercantilist policies, expecting that advancing English trade and shipping would strengthen their political and financial position. English merchants and chartered companies, such as the East India Company, Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, and Levant Company, calculated that economic primacy could be seized from the Dutch. They figured that a combination of English naval force and privateering would cripple the Dutch Republic and force the States General to agree to a favourable peace.[2]

This war, provoked in 1664, contained quite a few great English victories in battle such as James II's taking of the Dutch colony of New Netherland (present day New York), but also Dutch victories, such as the capture of the Prince Royal during the Four Days Battle in 1666 which was the subject of a famous painting by Willem van de Velde. However, the Raid on the Medway, in June 1667, ended the war with a Dutch victory. It is considered one of the most humiliating defeats in British military history:[3] a flotilla of ships led by Admiral de Ruyter sailed up the river Thames, broke through the defensive chains guarding the Medway, burned part of the English fleet docked at Chatham and towed away the Unity and the Royal Charles, pride and normal flagship of the English fleet. The greatly expanded Dutch navy was for numerous years after the world's strongest. The Dutch Republic was at the zenith of its power.

The English managed to capture about 450 Dutch merchantmen, far fewer than they expected. In 1665 many Dutch ships were intercepted, and Dutch trade and industry was hurt. The Dutch soon recovered as Dutch traders took precautions and benefited from the absence of the English fleet. Dutch maritime trade recovered from 1666 onward, but English commercial interests were badly hurt and King Charles faced virtual bankruptcy.[4]

The Dutch success made a major psychological impact throughout England, with London feeling especially vulnerable just a year after the Great Fire (which was generally interpreted in the Dutch Republic as divine retribution for Holmes's Bonfire). This, together with the cost of the war, of the Great Plague and the extravagant spending of Charles's court, produced a rebellious atmosphere in London. Clarendon ordered the English envoys at Breda to sign a peace quickly, as Charles feared an open revolt.

Third war (1672–1674)

Soon the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. However, as he was bound by the secret Treaty of Dover, Charles II was obliged to assist Louis XIV in his attack on The Republic in the Franco-Dutch War. When the French army was halted by the Hollandic Water Line (a defence system involving strategic flooding), an attempt was made to invade The Republic by sea. De Ruyter gained four strategic victories against the Anglo-French fleet and prevented invasion. After these failures the English parliament forced Charles to make peace.

Fourth war (1780–1784)

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 ended the 17th century conflict by placing William of Orange on the English throne as co-ruler with his wife Mary. This proved to be a pyrrhic victory for the Dutch cause. William's main concern had been getting the English on the same side as the Dutch in their competition against France. After becoming King of England, he granted many privileges to the English navy in order to ensure their loyalty and cooperation. William ordered that any Anglo-Dutch fleet be under English command, with the Dutch navy having 60% of the strength of the English.

The Dutch merchant elite began to use London as a new operational base. Dutch economic growth slowed. From about 1720 Dutch wealth ceased to grow. Around 1780 the per capita gross national product of the Kingdom of Great Britain surpassed that of the Dutch. Whereas in the 17th century the commercial success of the Dutch had inspired English jealousy and admiration, in the late 18th century the growth of British power, and the concurrent loss of Amsterdam's preeminence, led to Dutch resentment. When the Dutch Republic began to support the American rebels, this led to the fourth war, and the loss of the alliance made the Dutch Republic fatally vulnerable to the French. Soon it would be subject to regime change itself.

The Dutch navy was by now only a shadow of its former self, having only about twenty ships of the line, so there were no large fleet battles. The British tried to reduce the Republic to the status of a British protectorate, using Prussian military pressure and gaining factual control over the Dutch colonies, those conquered during the war given back at war's end. The Dutch then still held some key positions in the European trade with Asia, such as the Cape Colony, Ceylon and Malacca. The war sparked a new round of Dutch ship building (95 warships in the last quarter of the 18th century), but the British kept their absolute numerical superiority by doubling their fleet in the same time.

Although this war is technically an Anglo-Dutch war (as it was between Britain and the Netherlands), many respectable historians, such as Steven Pincus, argue that this later war stemmed from completely different causes and therefore should not be included in a discussion of these earlier wars.

Later wars

In the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars of 1793–1815, France reduced the Netherlands to a satellite and finally annexed the country in 1810. In 1797 the Dutch fleet was defeated by the British in the Battle of Camperdown. France considered both the extant Dutch fleet and the large Dutch shipbuilding capacity very important assets, but after the Battle of Trafalgar gave up its attempt to match the British fleet, despite a strong Dutch lobby to this effect. After the incorporation of the Netherlands in the French Empire, Britain took over most of the Dutch colonies, with the exception of Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Suriname (which they had captured in May 1804), the Dutch Antilles and the trading post at Dejima in Japan.

Some historians count the wars between Britain and the Batavian Republic and the Kingdom of Holland during the Napoleonic era as the Fifth and Sixth Anglo-Dutch wars.

See also

- British military history

- Dutch military history

- Netherlands – United Kingdom relations

- The Royal Navy

Notes

- ↑ Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic: its rise, greatness and fall, 1477-1806 (1995), p 713

- ↑ Gijs Rommelse, "Prizes and Profits: Dutch Maritime Trade during the Second Anglo-Dutch War," International Journal of Maritime History (2007) 19#2 pp 139-159.

- ↑ "It can hardly be denied that the Dutch raid on the Medway vies with the Battle of Majuba in 1881 and the Fall of Singapore in 1942 for the unenviable distinctor of being the most humiliating defeat suffered by British arms." – Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London (1974), p.39

- ↑ Rommelse, "Prizes and Profits: Dutch Maritime Trade during the Second Anglo-Dutch War," International Journal of Maritime History (2007) pp 139-159.

Further reading

- Boxer, Charles Ralph. The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century (1974)

- Bruijn, Jaap R. The Dutch navy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (U of South Carolina Press, 1993).

- Geyl, Pieter. Orange & Stuart 1641-1672 (1969)

- Hainsworth, D. R., et al. The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 (1998)

- Israel, Jonathan Ie. The Dutch Republic: its rise, greatness and fall, 1477-1806 (1995), pp 713-26, 766-76, 796-806. The Dutch political perspective.

- Jones, James Rees. The Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century (1996) online; the fullest military history.

- Kennedy, Paul M. The rise and fall of British naval mastery (1983) pp 47-74.

- Konstam, Angus, and Tony Bryan. Warships of the Anglo-Dutch Wars 1652-74 (2011) excerpt and text search

- Levy, Jack S., and Salvatore Ali. "From commercial competition to strategic rivalry to war: The evolution of the Anglo-Dutch rivalry, 1609-52." in The dynamics of enduring rivalries (1998) pp: 29-63.

- Messenger, Charles, ed. Reader's Guide to Military History (Routledge, 2013). 19-21.

- Ogg, David. England in the Reign of Charles II (2nd ed. 1936), pp 283–321 (Second War); 357-88 (Third War), Military emphasis.

- Palmer, M. A. J. "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea." War in history 4.2 (1997): 123-149.

- Padfeld, Peter. Tides of Empire: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West. Vol. 2 1654-1763. (1982).

- Pincus, Steven C.A. Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the making of English foreign policy, 1650-1668 (Cambridge UP, 2002).

- Rommelse, Gijs "Prizes and Profits: Dutch Maritime Trade during the Second Anglo-Dutch War," International Journal of Maritime History (2007) 19#2 pp 139–159.

- Rommelse, Gijs. "The role of mercantilism in Anglo-Dutch political relations, 1650–74." Economic History Review 63#3 (2010) 591-611.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anglo-Dutch wars. |

- Painting of Anglo-Dutch sea battle, Third War, at the National Maritime Museum, London (in Dutch), NL: Zeeburg nieuws.

- National Maritime Museum, London.

- Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyters' flagship 'The Seven Provinces' is being rebuilt in the Dutch town of Lelystad.

- A short history of the Anglo–Dutch Wars, Contemplator.