Shoeless Joe Jackson

| "Shoeless" Joe Jackson | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

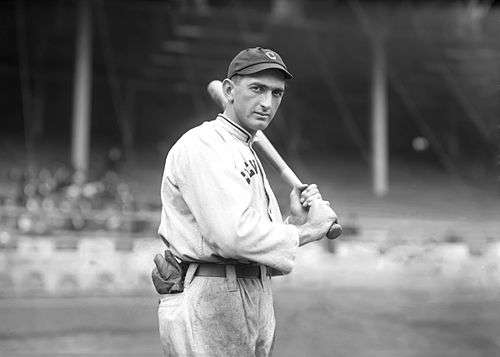

Jackson with the Naps in 1913 | |||

| Outfielder | |||

|

Born: July 16, 1887 Pickens County, South Carolina | |||

|

Died: December 5, 1951 (aged 64) Greenville, South Carolina | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| August 25, 1908, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 27, 1920, for the Chicago White Sox | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .356 | ||

| Hits | 1,772 | ||

| Home runs | 54 | ||

| Runs batted in | 785 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 15, 1888 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American outfielder who played Major League Baseball in the early part of the 20th century. He is remembered for his performance on the field and for his alleged association with the Black Sox Scandal, in which members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox participated in a conspiracy to fix the World Series. As a result of Jackson's association with the scandal, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Major League Baseball's first commissioner, banned Jackson from playing after the 1920 season despite exceptional play in the 1919 World Series, leading both teams in a statistical category and setting a series record. Since then, Jackson's guilt has been fiercely debated with new accounts claiming his innocence beckoning Major League Baseball to reconsider his banishment. As a result of the scandal, Jackson's career was abruptly halted in his prime, ensuring him a place in baseball lore forever.

Jackson played for three Major League teams during his 12-year career. He spent 1908–1909 as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics and 1910 with the minor league New Orleans Pelicans before joining the Cleveland Naps at the end of the 1910 season. He remained in Cleveland through the first part of 1915; he played the remainder of the 1915 season through 1920 with the Chicago White Sox.

Jackson, who played left field for most of his career, currently has the third-highest career batting average in major league history. In 1911, Jackson hit for a .408 average. It is still the sixth-highest single-season total since 1901, which marked the beginning of the modern era for the sport. His average that year also set the record for batting average in a single season by a rookie.[1] Babe Ruth said that he modeled his hitting technique after Jackson's.[2]

Jackson still holds the Indians and White Sox franchise records for both triples in a season and career batting average. In 1999, he ranked number 35 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. The fans voted him as the 12th-best outfielder of all-time. He also ranks 33rd on the all-time list for non-pitchers according to the win shares formula developed by Bill James.

Early life

Jackson was born in Pickens County, South Carolina, the oldest son in the family. His father George was a sharecropper; he moved the family to Pelzer, South Carolina, while Jackson was still a baby.[3] A few years afterwards the family moved to a company town called Brandon Mill, on the outskirts of Greenville, South Carolina.[4] An attack of measles almost killed him when he was 10. He was in bed for two months, paralyzed while he was nursed back to health by his mother.[5]

Starting at the age of 6 or 7, Jackson worked in one of the town's textile mills as a "linthead", a derogatory name for a mill hand.[4] Family finances required Joe to take 12-hour shifts in the mill, and since education at the time was a luxury the Jackson family couldn't afford, Jackson was uneducated.[4] His lack of education ultimately became an issue throughout Jackson's life. It even affected the value of his memorabilia in the collectibles market; because Jackson was illiterate, he often had his wife sign his signature. Consequently, anything actually autographed by Jackson himself brings a premium when sold, including one autograph which was sold for $23,500 in 1990 (equal to $43,000 today).[6] In restaurants, rather than ask someone to read the menu to him, he would wait until his teammates ordered and then order one of the items that he heard.[7]

In 1900, when he was 13 years old, his mother was approached by one of the owners of the Brandon Mill and he started to play for the mill's baseball team.[8] He was the youngest player on the team. He was paid $2.50 to play on Saturdays (equivalent to $71.00 today).[5] He was originally placed as a pitcher, but one day he accidentally broke another player's arm with a fastball. No one wanted to bat against him so the manager of the team placed him in the outfield. His hitting ability made him a celebrity around town. Around that time he was given a baseball bat which he named Black Betsy.[8] He was compared to Champ Osteen, another player from the mills who made it to the Majors.[8] He moved from mill team to mill team in search of better pay, even playing semi-professional baseball by 1905.[8]

Nickname

According to Jackson, he got his nickname during a mill game played in Greenville, South Carolina. Jackson had blisters on his foot from a new pair of cleats, which hurt so much that he took his shoes off before he was at bat. As play continued, a heckling fan noticed Jackson running to third base in his socks, and shouted "You shoeless son of a gun, you!" and the resulting nickname "Shoeless Joe" stuck with him throughout the remainder of his life.[9]

Professional career

Early professional career

1908 was an eventful year for Jackson. He began his professional baseball career with the Greenville Spinners of the Carolina Association, married 15-year-old Katie Wynn, and eventually signed with Connie Mack to play Major League Baseball for the Philadelphia Athletics.[9]

For the first two years of his career, Jackson had some trouble adjusting to life with the Athletics; reports conflict as to whether he just did not like the big city, or if he was bothered by hazing from teammates. Consequently, he spent a great portion of that time in the minor leagues. Between 1908 and 1909, Jackson appeared in just 10 games.[10] During the 1909 season, Jackson played 118 games for the South Atlantic League's Savannah Indians. He batted .358 for the year.[11]

Major League career

The Athletics gave up on Jackson in 1910 and traded him to the Cleveland Naps. He spent most of 1910 with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, where he won the batting title and led the team to the pennant. Late in the season, he was called up to play on the big league team. He appeared in 20 games and hit .387. In 1911, Jackson's first full season, he set a number of rookie records. His .408 batting average that season is a record that still stands and was good for second overall in the league behind Ty Cobb. His .468 on-base percentage led the league. The following season, Jackson batted .395 and led the American League in hits, triples, and total bases. On April 20, 1912, Jackson scored the first run in Tiger Stadium.[12] The next year, he led the league with 197 hits and a .551 slugging percentage.

In August 1915, Jackson was traded to the Chicago White Sox. Two years later, Jackson and the White Sox won the American League pennant and also the World Series. During the series, Jackson hit .307 as the White Sox defeated the New York Giants.

Jackson missed most of the 1918 season while working in a shipyard because of World War I. In 1919, he came back strongly to post a .351 average during the regular season and .375 with perfect fielding in the World Series. However, the heavily favored White Sox lost the series to the Cincinnati Reds. The next season, Jackson batted .382 and was leading the American league in triples when he was suspended, along with seven other members of the White Sox, after allegations surfaced that the team had thrown the previous World Series.

Black Sox scandal

After the White Sox lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, Jackson and seven other White Sox players were accused of accepting $5,000 each to throw the Series. In September 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate the allegations.

Jackson's 12 base hits set a Series record that was not broken until 1964,[13] and he led both teams with a .375 batting average. He committed no errors, and threw out a runner at the plate.[14] Assertions that the Reds hit an unusually high number of triples to Jackson's position in left field[15] are not supported by contemporary newspaper accounts, which recorded no Cincinnati triples at all to left field. The only two White Sox errors involving extra-base hits were committed by Shano Collins, in right field. (Collins was never accused in the scandal, and in fact was listed in the indictments as a wronged party—the victim of $1,784 in lost earnings due to the actions of those charged.[16])

Some news accounts quoted Jackson, during grand jury testimony on September 28, 1920, admitting that he agreed to participate in the fix:[17]

| “ | When a Cincinnati player would bat a ball out in my territory I'd muff it if I could—that is, fail to catch it. But if it would look too much like crooked work to do that I'd be slow and make a throw to the infield that would be short. My work netted the Cincinnati team several runs that they never would have had if we had been playing on the square. | ” |

No such testimony appears in the actual stenographic record of Jackson's grand jury appearance.[18]

After the grand jury returned its indictments, Charley Owens of the Chicago Daily News wrote a regretful tribute headlined, "Say it ain't so, Joe."[19] The phrase became legend when another reporter later erroneously attributed it to a child outside the courthouse:

When Jackson left the criminal court building in the custody of a sheriff after telling his story to the grand jury, he found several hundred youngsters, aged from 6 to 16, waiting for a glimpse of their idol. One child stepped up to the outfielder, and, grabbing his coat sleeve, said:

"It ain't true, is it, Joe?"

"Yes, kid, I'm afraid it is", Jackson replied. The boys opened a path for the ball player and stood in silence until he passed out of sight.

"Well, I'd never have thought it," sighed the lad.[20]

In an interview in SPORT nearly three decades later, Jackson confirmed that the legendary exchange never occurred.[21]

In 1921, a Chicago jury acquitted Jackson and his seven teammates of wrongdoing. Nevertheless, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the newly appointed Commissioner of Baseball, imposed a lifetime ban on all eight players. "Regardless of the verdict of juries", Landis declared, "no player that throws a ballgame; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball."[22]

Dispute over Jackson's guilt

Jackson spent most of the last 30 years of his life proclaiming his innocence, and evidence has surfaced that casts significant doubt on his involvement in the fix. Jackson reportedly refused the $5,000 bribe on two separate occasions — despite the fact that it would effectively double his salary — only to have teammate Lefty Williams toss the cash on the floor of his hotel room. Jackson then reportedly tried to tell White Sox owner Charles Comiskey about the fix, but Comiskey refused to meet with him.[23] Unable to afford legal counsel, Jackson was represented by team attorney Alfred Austrian—a clear conflict of interest. Before Jackson's grand jury testimony, Austrian allegedly elicited Jackson's admission of his supposed role in the fix by plying him with whiskey.[14] Austrian was also able to persuade the nearly illiterate Jackson to sign a waiver of immunity from prosecution.[23] Years later, the other seven players implicated in the scandal confirmed that Jackson was never at any of the meetings. Williams said that they only mentioned Jackson's name to give their plot more credibility. Jackson's performance during the series itself lends further credence to his assertions.[14] A 1993 article in The American Statistician reported the results of a statistical analysis of Jackson's contribution during the 1919 World Series, and concluded that there was "substantial support to Jackson's subsequent claims of innocence".[24]

An article in the September 2009 issue of Chicago Lawyer magazine argued that Eliot Asinof's 1963 book Eight Men Out, purporting to confirm Jackson's guilt, was based on inaccurate information; for example, Jackson never confessed to throwing the Series as Asinof claimed. Further, Asinof omitted key facts from publicly available documents such as the 1920 grand jury records and proceedings of Jackson's successful 1924 lawsuit against Comiskey to recover back pay for the 1920 and 1921 seasons. Asinof's use of fictional characters within a supposedly non-fiction account added further questions about the historical accuracy of the book.[25]

Jackson remains on MLB's ineligible list, which automatically precludes his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1989, MLB Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti declined to reinstate Jackson because the case was "now best given to historical analysis and debate as opposed to a present-day review with an eye to reinstatement."[26]

In November 1999, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution lauding Jackson's sporting achievements and encouraging MLB to rescind his ineligibility. The resolution was symbolic, since the U.S. government has no jurisdiction in the matter. Commissioner Bud Selig stated at the time that Jackson's case was under review, but no decision was issued during Selig's tenure.[27]

In 2015, the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum formally petitioned Commissioner Rob Manfred for reinstatement, on grounds that Jackson had "more than served his sentence" in the 95 years since his banishment by Landis. Manfred denied the request after an official review. "The results of this work demonstrate to me that it is not possible now, over 95 years since those events took place and were considered by Commissioner Landis, to be certain enough of the truth to overrule Commissioner Landis' determinations", he wrote.[26]

Career statistics

See baseball statistics for an explanation of these statistics.

| G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | R | RBI | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,332 | 4,981 | 1,772 | 307 | 168 | 54 | 873 | 785 | 519 | 158 | .356 | .423 | .517 |

Later life

During the remaining 20 years of his baseball career, Jackson played with and managed a number of semi-professional teams, most located in Georgia and South Carolina.[28] In 1922, Jackson moved to Savannah, Georgia, and opened a dry cleaning business with his wife.

In 1933, the Jacksons moved back to Greenville, South Carolina. After first opening a barbecue restaurant, Jackson and his wife opened "Joe Jackson's Liquor Store", which they operated until his death. One of the better known stories of Jackson's post-major league life took place at his liquor store. Ty Cobb and sportswriter Grantland Rice entered the store, with Jackson showing no sign of recognition towards Cobb. After making his purchase, the incredulous Cobb finally asked Jackson, "Don't you know me, Joe?" Jackson replied, "Sure, I know you, Ty, but I wasn't sure you wanted to know me. A lot of them don't."[29]

As he aged, Jackson began to suffer from heart trouble. In 1951, at the age of 64, Jackson died of a heart attack.[28] He was the first of the eight banned players to die, and is buried at Woodlawn Memorial Park. Prior to his death, he was scheduled to be interviewed on television to set the record straight about reports that he was living in poverty, but died before the interview could take place. He had no children, but he and his wife raised two of his nephews.

Films and plays

Shoeless Joe has been depicted in a few films in the late 20th century. Eight Men Out, a film directed by John Sayles, based on the Eliot Asinof book of the same name, details the Black Sox scandal in general and has D. B. Sweeney portraying Jackson.

The Phil Alden Robinson film Field of Dreams, based on Shoeless Joe by W. P. Kinsella, stars Ray Liotta as Jackson. Kevin Costner plays an Iowa farmer who hears a mysterious voice instructing him to build a baseball field on his farm so Shoeless Joe can play baseball again. (Liotta portrays Jackson as batting right-handed and throwing left-handed, although Jackson actually batted left and threw right.)

Jackson's nickname was worked into the musical play Damn Yankees. The lead character, baseball phenomenon Joe Hardy, alleged to be from a small town in Missouri, is dubbed by the media as "Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, MO." The play also contains a plot element alleging that Joe had thrown baseball games in his earlier days.

Jackson was also an inspiration, in part, for the character Roy Hobbs in The Natural. Hobbs has a special name for his bat (as Jackson did), and is offered a bribe to throw a game. In the book (but not the film), a youngster pleads with Hobbs, "Say it ain't true, Roy!"

Shoeless Joe is a character in the song "Kenesaw Mountain Landis", by Jonathan Coulton, although the song takes many liberties with the story for comedic effect.

Legacy

Though Jackson was banned from Major League Baseball, statues and parks have been constructed in his honor. One of the landmarks built for him was a memorial park in Greenville, Shoeless Joe Jackson Memorial Park.[30][31] A life-size statue of Jackson, created by South Carolina sculptor Doug Young, also stands in Greenville's West End.

In 2006, Jackson's original home was moved to a location adjacent to Fluor Field in downtown Greenville. The home was restored and opened in 2008 as the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum.[32] The address is 356 Field Street, in honor of his lifetime batting average. The restoration and move was chronicled on The Learning Channel's reality show "The Real Deal" episode "A Home Run for Trademark" which aired March 31, 2007. Richard C. Davis, the owner of Trademark Properties hired Josh Hamilton as the construction foreman. In a bit of irony, the show also chronicled Hamiliton's attempt to rejoin baseball after a one-year drug abuse suspension and 3-year absence.[33]

Jackson was inducted into the Shrine of the Eternals by the Baseball Reliquary.

Jackson's first relative to play professional baseball since his banishment was catcher Joseph Ray Jackson. The great-great-grand nephew of Shoeless Joe batted .386 for The Citadel in 2013 and was then drafted by the Texas Rangers. Later that year, he made his professional debut with the Northwest League's Spokane Indians.[34][35][36]

See also

- List of Chicago White Sox team records

- List of Cleveland Indians team records

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players with a .400 batting average in a season

- List of Major League Baseball career slugging percentage leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career OPS leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career batting average leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career on-base percentage leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball triples records

- List of people banned from Major League Baseball

References

- ↑ Although he was in the majors as early as 1908, Major League rules at the time stipulated that a player was considered a rookie until he has had more than 130 at-bats in a season.

- ↑ "The Baseball Page". thebaseballpage.com/players/jacksjo01.php. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ↑ David L. Fleitz. Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson. McFarland. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7864-3312-4.

- 1 2 3 Fleitz p. 7

- 1 2 Fleitz p. 9

- ↑ "Joe Jackson Autograph Auctioned for $23,500". The Nevada Daily Mail. Associated Press. December 9, 1990. p. 1.

- ↑ Honig, Donald. The Man in the Dugout.

- 1 2 3 4 Fleitz p. 10

- 1 2 "Chicago Historical Society". chicagohs.com. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ↑ "JoeJackson.com Biography". shoelessjoejackson.com. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ↑ "Shoeless Joe Jackson Minor League Statistics & History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ The Final Season, p.5, Tom Stanton, Thomas Dunne Books, An imprint of St. Martin's Press, New York, 2001, ISBN 0-312-29156-6

- ↑ "All-time and Single-Season World Series Batting Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- 1 2 3 Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ↑ Neyer, Rob. Say it ain't so ... for Joe and the Hall. ESPN Classic.com. 30 August 2007.

- ↑ Indictment & Bill of Particulars in People of Illinois v Cicotte (The "Black Sox" Trial). umkc.edu archive, retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Attell Says He Will Have Plenty to Say", Minnesota Daily Star, September 29, 1920, pg. 5

- ↑ In the Matter of the Investigation of Alleged Baseball Scandal. September 28, 1920.

- ↑ "Black Sox" trial, 1921: "Say it ain't so, Joe". jrank.org, retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ "'It Ain't True, Is It, Joe?' Youngster Asks", Minnesota Daily Star, September 29, 1920, p. 5

- ↑ "Shoeless Joe Jackson Virtual Hall of Fame – 1949 Sport Magazine Interview". blackbetsy.com.

- ↑ "The Chicago Black Sox banned from baseball". ESPN. November 19, 2003. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- 1 2 Plummer, William (August 7, 1989). "Shoeless Joe: His Legend Survives the Man and the Scandal". People. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Bennett, J. (1993) Did Shoeless Joe Jackson throw the 1919 World Series. The American Statistician 47(4), pp. 241–250.

- ↑ Voelker, Daniel J.; and Paul A. Duffy. "Black Sox: 'It ain't so, kid, it just ain't so'", Chicago Lawyer, 1 September 2009.

- 1 2 "MLB won't reinstate Shoeless Joe Jackson". ESPN. September 1, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. House Backs Shoeless Joe". CBS.com. November 8, 1999. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- 1 2 "Joe Jackson Timeline". blackbetsy.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ↑ "Ty Cobb & Joe Jackson story" (PDF). www.pde.state.pa.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2006. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ↑ " "Shoeless Joe Jackson Memorial Park". Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ↑ Josh Pahigian (2007). The Ultimate Minor League Baseball Road Trip: A Fan's Guide to AAA, AA, A, and Independent League Stadiums. Globe Pequot. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-1-59921-627-0.

- ↑ "Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum and Baseball Library". Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Hooray for Trademark Properties and Richard Davis!!!". Fraud Files Forensic Accounting Blog.

- ↑ Caple, Jim. "Meet Joe Jackson, shoes 'n' all". espn.go.com. March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Hartsell, Jeff. "Texas Rangers take Citadel's Joe Jackson; Mariners pick C of C pitcher Jake Zokan". postandcourier.com. June 8, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Joe Jackson Minor League Statistics & History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

Bibliography

- Eight Men Out, by Eliot Asinof

- "Shoeless: The Life And Times of Joe Jackson", by David L. Fleitz (2001, McFarland & Company Publishers)

- Say It Ain't So, Joe!: The True Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson, by Donald Gropman

- Shoeless Joe & Me (HarperCollins, 2002) by Dan Gutman

- Shoeless Joe, a novel by W. P. Kinsella

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Shoeless Joe Jackson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shoeless Joe Jackson. |

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Shoeless Joe Jackson at Find a Grave

- ShoelessJoeJackson.com – Jackson's official website

- Joe Jackson Plaza in Greenville, South Carolina

- The letter written by Commissioner Landis banning Jackson from baseball