Østfold Line

| Østfold Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NSB Class 73 train south of Vestby Station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | Østfoldbanen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Norwegian railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini |

Oslo Central Station Kornsjø Station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 24 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 2 January 1879 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Norwegian National Rail Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Freight and passenger | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 171 km (106 mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | Single or double | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 15 kV 16 2⁄3 Hz AC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | Max. 160 km/h (99 mph) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Østfold Line (Norwegian: Østfoldbanen) is a 170-kilometer (110 mi) railway line which runs from Oslo through the western parts of Follo and Østfold to Kornsjø in Norway. It continues through Sweden as the Norway/Vänern Line. The northern half is double track and the entire line is electrified. It serves a combination of commuter, regional and freight trains and is the main rail corridor south of Norway. The Eastern Østfold Line branches off at Ski Station and runs 79 kilometers (49 mi) before rejoining at Sarpsborg Station.

The line opened as the Smaalenene Line (Smaalenenebanen) on 2 January 1879. Stations were designed by Peter Andreas Blix. It was the first railway in Norway to predominantly build bridges and viaducts with iron. The line underwent upgrades from 1910 through 1940 in which the section from Oslo to Ski received double track, the permitted weight and speeds were increased and the line was electrified. From 1989 to 1996 the section from Ski to Sandbukta received double track and speeds of 160 km/h (99 mph). Work has since 2015 been under way to upgrade most of the line to high-speed. This includes the Follo Line which will offer a direct route from Oslo to Ski by 2021, and new tracks at least as far as Halden by 2030.

Route

The Østfold Line runs from Oslo Central Station through the counties of Oslo, Akershus and Østfold to the Norway–Sweden border at Kornsjø, covering a distance of 170.1 kilometers (105.7 mi). The line generally follows the west shore of the Oslofjord until Halden, where it passes through major towns of Ski, Ås, Vestby, Moss, Fredrikstad, Sarpsborg. The line is standard gauge and electrified at 15 kV 16 2⁄3 Hz AC. It is double track from Oslo to Sandbukta north of Moss, a distance of 57 kilometers (35 mi), as well as 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) past Rygge Station. There are three railway stations and three freight terminals along the line. At Kornsjø the line continues through Sweden as the Norway/Vänern Line.[1]

The term Østfold Line is most commonly used to describe the section from Oslo via Moss to Kornsjø. This is sometimes also referred to as the Western Line. Both uses exclude the section from Ski via Askim to Sarpsborg, known as the Eastern Line. At other times Østfold Line is used to refer to the entire network, both via Moss and Askim. Sometimes Western Line is used to only describe the section from Ski via Moss to Sarpsborg. Although the eastern and western branches were initially planned as equals, the western has become dominant due to it always having had a higher standard and serving all through trains.[2]

At Loenga in Oslo the line branches, the main part heading to the Central Station and the Loenga–Alnabru Line branching off to Alnabru Freight Terminal. This section is only used by freight trains.[3] The Eastern Østfold Line is 78.9 kilometers (49.0 mi) and runs from Ski to Sarpsborg via the municipalities of Tomter, Hobøl, Eidsberg, Mysen and Rakkestad. Normally only serving commuter trains, it can be used as a bypass when needed.[4]

History

Planning

The lack of early interest in a railway in Østfold was caused by the ice-free Oslofjord and the perceived non-necessity of build a line where a suitable waterway already existed.[5] Proposals for a railway through the county then known as Smaalenene were first launched with two independent letters to the editor in 1866. They exemplified the debate which would follow, with one proposing a route along the coast through the larger coastal towns, while the other proposed an inner route via Askim and Rakkestad.[6] Preliminary surveys were carried out the following year, which also investigated two routes to the Swedish border, one via Tistedalen and one along Iddefjord. The government was at first less enthusiastic, in part because they were concerned that no line would be build on the Swedish side.[7]

By 1872 the disagreement over an interior or coastal route was raging and a compromise was proposed in which the line would be built with two branches. [8] The government recommended a twin-armed line on 5 April 1873 and was approved in Parliament on 5 June. Detailed surveying was led by Carl Abraham Pihl and concluded on 31 March 1874. The route was still controversial, especially relating to how Fredrikstad should be served. The main line could be shortened by 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) if the town was served with a branch line.[9] With increasing cost estimates, Parliament decided to reduce the standard on the Eastern Line. There was also a controversy if that line should bypass Mysen.[10]

In Halden there was a significant opposition to the line, as there was worry that it would capture lumber traffic which would otherwise run to Halden. Traders and politicians there were more concerned with being connected with the Swedish province of Dalsland, from which a large part of the town's lumber export originated. To secure the Swedish part of the link, the Dalsland Line was built as a private railway with eighty percent Norwegian capital and its head office in Halden.[11]

Construction

Construction commenced in 1874, initially only on the section from Oslo to Halden. Work was subdivided into eleven sections on the Western Line and four on the Eastern Line. The former received a rail weight of 30 kilograms per meter (60 lb/ft).[12] Work on the Estern Line did not start until 1877. It received a track weight of only 25 kilograms per meter (50 lb/ft). A recession hit in 1877 and the government stopped all construction for a period, initially only continuing it on the Western Line.[13] Most of the workforce were Swedish immigrants. Groundwork was conducted directly by the railway based on accords, with the track was laid by contractors.[12]

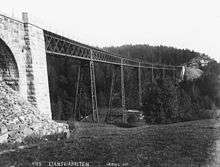

The Østfold Line was the first railway in Norway were all bridges were built with iron. This allowed for the construction of viaducts at some places, which changed the mass balance allowing the line to follow a better gradient. Two of the most prominent were the Ljan Viaduct and the Hølen Viaduct. The latter was the first in the world to use the pendulum pillar principal. The bridges and viaducts were all designed by Axel Jacob Petersson.[14]

.jpg)

The Western Line from Oslo to Halden was taken into revenue service on 2 January 1879.[15] However, the official opening did not take place until 18 July. By then the rail connection onward to Gothenburg had been completed.[16] Construction of the Eastern Line was delayed and was opened in stages between 18 July and 24 November 1882.[17]

Early operations

The first rolling stock consisted of eight NSB Class 9 steam locomotives for passenger train, three NSB Class 10 units for freight trains[18] and two NSB Class 14 locos.[19] Passenger cars were at first 60 compartment coaches.[20] A commuter train service was introduced from Oslo to Ljan Station from 1883, allowing the areas of Nordstrand to opened up to large-scale housing.[21] The railway allowed for faster postal services and the trains carried markers with the weather forecast, which was announced at the stations.[22] A direct international train service was not introduced until 1 July 1886, when a direct service to Gothenburg and Hamburg was introduced. Travel time to Copenhagen was at this time twenty and a half hours. The following year sleeper cares were introduced.[23]

The commuter traffic increased and in 1893 a new commuter station was opened at Kolbotn.[24] Two branch lines were built from Sarpsborg. A branch to Borregaard opened in 1891 and the Hafslund Line opened eight years later.[25] To avail the problem in Oslo with human manure, depots were built at Drømtorp, Ås and Vestby to give farmers access to the resource. Manure trains ran until 1929.[26] Construction of interlocking systems started on some of the busiest stations in 1897, although fail-safe functionality was not available until the 1920s.[27] A faster inter-Scandinavian service was introduced in 1900, cutting travel time to Copenhagen to 16 hours and 20 minutes.[28] The higher demands caused the railway to order nine new NSB Class 27 locomotives, delivered between 1910 and 1916, which allowed the maximum speed on the line to increase from 70 to 75 km/h (43 to 47 mph).[29] NSB introduced Ea 1, an accumulator electric locomotive, on local services between Fredrikstand and Skjeberg in 1916, where it remained in use until 1920.[30]

Line upgrades

As the main international railway out of Norway, the Østfold Line had some of the highest demands for speed and axle loads. In an effort to increase train weights and speeds, the Norwegian State Railways approved an upgrade plan in 1910 which was initially to be completed by 1919. All bridges and track was to be upgraded to tolerate a higher train weight.[31] The break-out of the First World War led to material and funding shortages,[32] and the upgrades were not completed until a new Sarp Bridge was finished in 1930.[33]

The line was originally named the Smaalenene Line (Smaalenenebanene), with the spelling changing to Smålenene (Smålenenebanen) in 1921. During this period it was also commonly known as the South Line (Sydbanen), although this was never official. As the line was named for the county, it changed its name after the county changed its name from Smålenene to Østfold.[34]

Parliament approved double track from Oslo to Ljan in 1916. Construction took its time and opened in two stages, from Bekkelaget to Ljan on 1 June 1924 and from Oslo Ø to Bekkelaget on 15 May 1929.[35] South of Ljan the line crossed the Ljan Viaduct, which could not be upgraded to the new standards. A new double-tracked line had to be built around,[36] which opened on 15 February 1925.[37] By the 1930s the railway was meeting increased competition from buses and trucks. Although slower, they offered more pick-up locations than the train. NSB therefore decided that the Østfold Line, and especially the section closest to Oslo, needed to receive increased capacity, electric traction and more stations.[38] Double tracking continued southwards, opening to Kolbotn on 15 December 1936 and to Ski on 14 May 1939.[34] Meanwhile, NSB introduced gasoline railcars which stopped at the new flag stops.[39]

Electrification was carried out in several smaller steps, with the fist part from Oslo Ø to Ljan completed on 9 December 1936 and the last section from Sarpsborg to Halden, on 11 November 1940.[34] NSB Class 66 was introduced as an express servie on the Østfold Line, running a round trip from Oslo to Halden each day, bringing travel time down to two hours.[40] This lasted until 1956, when they were replaced with the slower NSB Class 65.[41] The international trains were from 1948 served with the Swedish State Railways' SJ X5 units, able to run from Oslo to Copenhagen in less than ten hours. The fast service was named Skandiapilen.[42] A landslide in 1953 washed away part of the track past Bekkelaget, resulting in the Bekkelaget Tunnel opening there five years later.[43] The regional traffic received the new NSB Class 68 multiple units from the mid 1950s.[44] A regular train with pyrite started running in 1966, hauling up to 600,000 tonnes per year from Hjerkinn on the Dovre Line to Borregaard. They remained until the 1990s.[45]

Double track almost to Moss

By the 1960s it was becoming evident that the infrastructure was outdated.[46] A particular problem were the many level crossings which were a safety hazard,[47] causing reduced speed, especially between Ski and Moss. Capacity was also used up and the section was the busiest section of single track in the country.[48] Already during the 1950s NSB proposed building double track, but this was dismissed by Parliament.[49] To avail the situation NSB introduced its InterCity Express services in 1983. This involved limiting stops to Rygge, Råde, Fredrikstad, Saprsborg and Halden south of Moss, causing a large number of stations to be closed.[48]

Upgrade plans between Ski and Moss were revitalized during the 1980s. Especially at Vestby Station had reliability issues and there was a need for new passing loop at Tveter Station and Kjenn Station. However, this would not be sufficient to meet future needs, and in 1985 Parliament passed the construction of a double track from Tveter via Vestby to Kjenn.[49] These plans were initially proposed as merely doubling the track to increase capacity, but NSB soon started looking at also raising the speed and standard. From Rustad to Smørbekk the route was planned and placed parallel to European Road E6. As the planning progressed, NSB gradually increased the dimensioning, so that the last planned section was capable of 200 km/h (120 mph).[50]

The first part of the double track, from Tveter to Vestby, was opened on 30 November 1989. The whole section cost 1.6 billion kroner and was opened for service on 22 October 1996. It was the first railway line to permit such high speeds in Norway.Due to disagreements with the Moss City Council on the route through the city, the double track stopped short at Sandbukta, 1.5 km (0.93 mi) north of Moss.[49] NSB Class 70 trains were introduced on the InterCity Express services in 1994, replaced by NSB Class 73 from 2003.[51]

On 28 June 2000, a new 7-kilometer (4.3 mi) section of double track was opened past Rygge Station. Including a full upgrade of the station, 21 road crossings were removed. The 500-million-kroner project reduced travel time between Moss and Fredrikstad by seven minutes.[52] Since 2007, Rygge Station has also served as an airport rail link via a shuttle bus to the nearby Moss Airport, Rygge.[53]

Services

_-_2011-09-10_at_15-43-56.jpg)

Passenger train services are provided by the Norwegian State Railways (NSB). The L2 service calls at all stations between Oslo S and Ski. The L21 and L22 services make one stop between Oslo and Ski, then L21 continues onward on the Western Line calling at Ås, Vestby, Sonsveien and Kambo before terminating at Moss. L22 runs along the Eastern Line, calling at six stations before Mysen. R20 only stops at Ski before Moss, then serves Rygge, Råde, Fredrikstad, Sarpsborg and Halden. In regular hours L2 operates with two hourly services, while the others operate with one hourly services. There are additional rush-hour trains. Three R20-services continue onward to Gothenburg Central Station each day.

Architecture

Peter Andreas Blix was hired as the national railway architect in 1873 and awarded the task of designing the stations on the Østfold Line. His designs drew inspiration from Medieval architecture, Gothic architecture and contemporary English villa styles. He let the interior plans dominate the outer shape and avoided symmetry. Most of the station buildings were in wood and standardized designs. Stations which were expected to have larger traffic received a separate goods sheds. The four main towns received brick stations. Halden Station was the most prominent, with an exterior which drew elements from a Medieval fortresses inspired from Fredriksten Fortress and the town's role as a border town. Moss, Fredrikstad and Sarpsborg received the same design with three gables on each facade.[54]

Future

The Østfold Line is part of the InterCity Triangle and one of four prioritized lines in Norway being upgraded to high-speed rail.[55] The entire section from Oslo to Halden is scheduled to be upgraded by 2030. The first step is construction of the Follo Line, a 22-kilometer (14 mi) new line which will run in a tunnel almost the entire length from Oslo to Ski. It will allow all passenger trains heading south of Ski to save 11 minutes, and free up capacity on the old double track for more commuter and freight trains. Construction started in 2015 and the Follo Line is scheduled for completion in 2021. It may also include a new connection to Kråkstad. Once completed, the old double track from Oslo to Ski will receive an overhaul.[56]

Upgrades southwards are split into four phases. By 2020 the missing doubel-track link from Sandbukta via a new Moss Station to Haug is scheduled for completion. The line from Haug to Seut north of Fredrikstad is planned to be finished by 2024, two years before the double track to Sarpsborg. The final stage to Halden is scheduled for completion in 2030.[55] The National Rail Administration is working on possibilities of expanding the double track further south and in conjunction with Swedish authorities complete a high-speed link between Oslo and Gothenburg. On the Swedish side the final 78 kilometers (48 mi) to Öxnered is already finished.[57]

The Østfold Line has the largest potential for an increase in freight traffic, with an estimated eleven trains per direction per day. These include freight trains to Götaland in Sweden, including a shuttle service to the Port of Gothenburg. Services could also run to Denmark and further south. Two steep hills, Brynsbakken on the Loenga–Alnabru Line and Tistedalsbakken south of Halden are currently major hindrances. Proposals have been made to build new lines to bypass these hills. One alternative to the south is to build a new railway from around Berg to Skee on the Bohus Line in Sweden. The capacity through the Western Line will be so large, especially during rush hour north of Moss, that it is possible that all freight trains may be routed via the Eastern Line. This will probably also mean that the existing railway between Sarpsborg and Halden will be kept, although it will probably be demolished north of Sarpsborg.[57][58]

The signaling system is scheduled to be renewed and replaced with the European Train Control System, with planned competition in 2030.[59]

References

- ↑ "Østfoldbanen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016.

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 151

- ↑ Bjerke & Holom: 60

- ↑ "Østfoldbanen, østre linje" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 17

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 17

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 19

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 20

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 22

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 23

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 25

- 1 2 Langård & Ruud: 24

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 26

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 30

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 50

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 54

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 58

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 44

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 46

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 47

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 56

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 59

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 62

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 78

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 80

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 82

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 89

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 92

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 98

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 108

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 93

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 94

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 120

- 1 2 3 Bjerke & Holom: 37

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 113

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 117

- ↑ Bjerke & Holom: 41

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 121

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 127

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 140

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 141

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 147

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 160

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 163

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 168

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 161

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 162

- 1 2 Langård & Ruud: 172

- 1 2 3 Holom, Finn (1996). "Dobbeltspor Ski–Moss fullføres". På Sporet. 88: 4–5.

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 185

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 177

- ↑ Norwegian National Rail Administration (26 June 2000). "Dobbeltspor åpnet forbi Rygge stasjon" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 7 September 2002. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ↑ Norwegian National Rail Administration. "Rygge". Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ Langård & Ruud: 36

- 1 2 Kjelland, Kathrine (5 September 2014). "Østfoldbanen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration.

- ↑ "Follobanen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration. 29 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Huvudrapport Oslo–Göteborg Uvikling av jernbanen i korridoren" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration / Swedish Transport Administration. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2016.

|archive-url=is malformed: save command (help) - ↑ Klemetzen, Hedda (24 May 2016). "Norsk-svensk enighet om jernbane over grensen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian National Rail Administration. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016.

- ↑ "ERTMS – National implementation plan" (PDF). Norwegian National Rail Administration. pp. 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Østfoldbanen. |

- Bjerke, Thor; Holom, Finn (2004). Banedata 2004 (in Norwegian). Hamar / Oslo: Norwegian Railway Museum / Norwegian Railway Club. ISBN 82-90286-28-7.

- Langård, Geir-Widar; Ruud, Leif-Harald (2005). Sydbaneracer og Skandiapil – Glimt fra Østfoldbanen gjennom 125 år (in Norwegian). Oslo: Norwegian Railway Club. ISBN 978-82-90286-29-8.